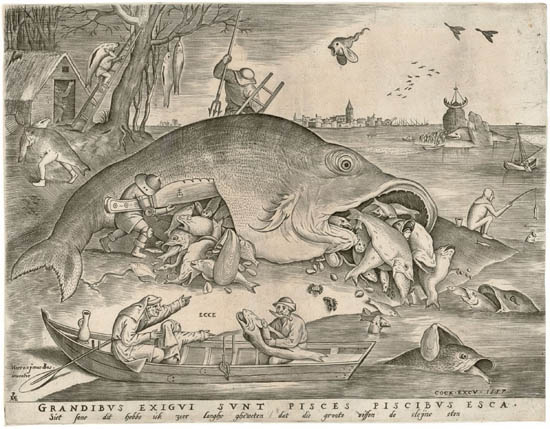

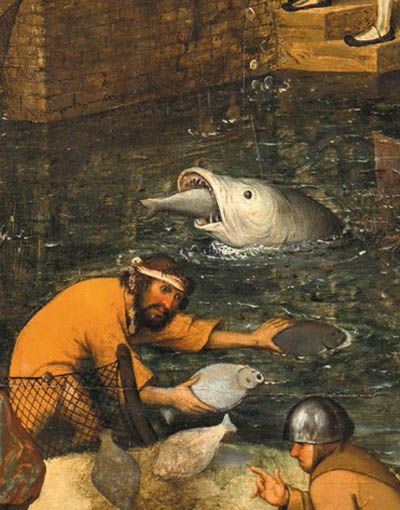

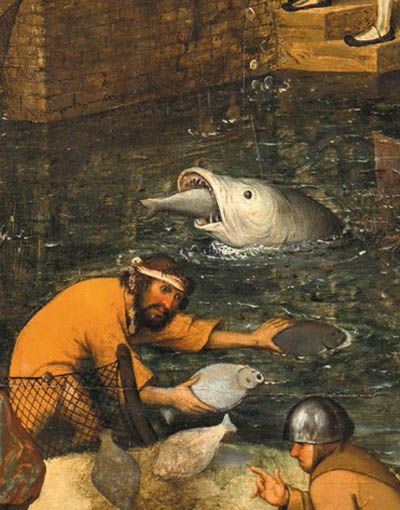

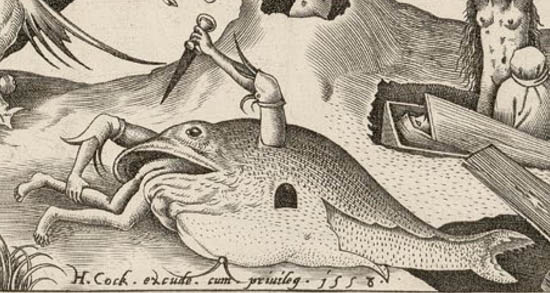

What would there be left in the picture if we took the big fish out of it? Basically nothing: the poor fishing hut on the left and the harbor town on the horizon, as well as the open sea bay between them, with a large, formless sandy beach. The landscape apparently was created to be a worthy frame for the matchless prey, the Great Fish, which is being cut open by a Liliputian man with a knife far greater than himself. From the stomach and mouth of the Fish, as if the blade of the knife also cut its throat, big fish-

matrioshki are pouring out, those that had been swallowed by the Fish, and which immediately before that, or already in its stomach, tried to swallow further fishes. The pieces of the prey falling into the sea are awaited and immediately swallowed by other fishes, as by the

seals on the fish market, and there is even a fish that come flying in for its share. The paroxysm of this gobbling frenzy grew to the point that even the mussels try to swallow fishes, even though they would think twice at this in their natural habitat. At the bottom of the picture, in a fishing boat, an oarsman points to the spectacle to his son: ECCE, and in the Flemish-language Italic inscription at the very bottom he shares with him the basic experience of his life:

Look, my son, I have known for a long time that big fish eat small fish. The same is said by the Latin legend, in hexameter: “GRANDIBUS EXIGUI SUNT PISCES PISCIBUS ESCA” –

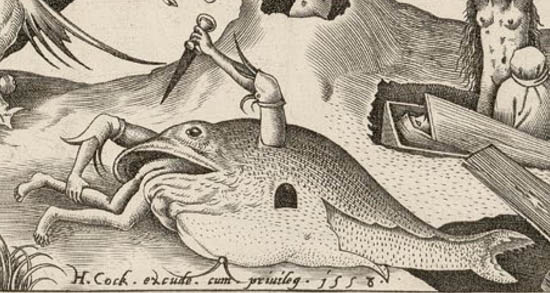

small fishes serve as food for big fishes. And a much later version of this 1557 print, published by

Jan Galle, active in Antwerp between 1620 and 1670, who even adds a trilingual explanation over the image, so that nobody can misunderstand the metaphor:

“OPPRESSION OF THE POOR. The rich suppress you with their power. Letter of James, 2:6.”

If the Fish – and the large fishes swallowed by it – illustrate this basic injustice, then it is possible that the Knife ripping its stomach, with its representation of the world in the form of a royal insignia on its blade, like the one usually held by Christ on the scenes of the Last Judgment, represents the ultimate justice.

Who is the author of the picture? The inscription gives two signatures. To the left:

“Hieronymus Bos. inventor”, and under it: “PAME”, while to the right: “COCK EXCU[DIT], 1557”. This means that the design is by Hieronymus Bosch, and the print was made by Cock in 1557. Neither of which is true. That Cock was not the engraver is proved by the monogram PAME, which indicates Pieter van der Heyden: he was one of the permanent engravers of Hieronymus Cock, the greatest print publisher of Antwerp. Thus, Cock boasted with the authorship of the print not as its master, but as its publisher. But neither can the original drawing be attributed to Bosch. It is akin to his style, but the usual composite monsters are missing (except for the fish next to the hut, which tries to get away with its prey on two legs).

The Albertina in Vienna, however, preserves the original drawing which served as a model for the print (inv. no. 7875). And this, rather than the signature of Bosch, bears that of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Here he writes his name with an

h, but soon he will drop it, and only his sons Pieter the Younger and Jan will return to the form Brueghel.

And Bruegel also uses this motif for one of the scenes in his “Netherlandish proverbs” of 1559.

In 1556, the young – perhaps thirty years old – Pieter Bruegel the Elder just recently returned home from his Italian study trip, where he improved his draughtmanship and made a lot of sketches, especially of the mountainous landscapes, which were unknown and attractive to the public in the Netherlands. He was looking for a living in Antwerp, which was the center not only of trade, but also of the art market of the contemporary world. In 1540 the first European permanent painting and print gallery was opened here, to which three hundred masters of the city delivered their products, and these reached such far away places as, for example, the Armenian cathedral in Isfahan, where the walls were decorated with frescoes made after biblical prints from Antwerp. One of the city’s best-selling art dealers, Hieronymus Cock, opened in 1548 his publishing house

At the Four Winds (In de Vier Winden), where highly sought-after prints were printed on the device, and for this, he sorely needed talented draughtsmen. As the young Bruegel arrived from Italy, he immediately contracted with him (and perhaps he already supported his Italian trip), and from then on they produced together a multitude of successful series of prints, from the

Large Landscapes to

The Seven Deadly Sins and Seven Virtues, which promoted the reputation of both of them.

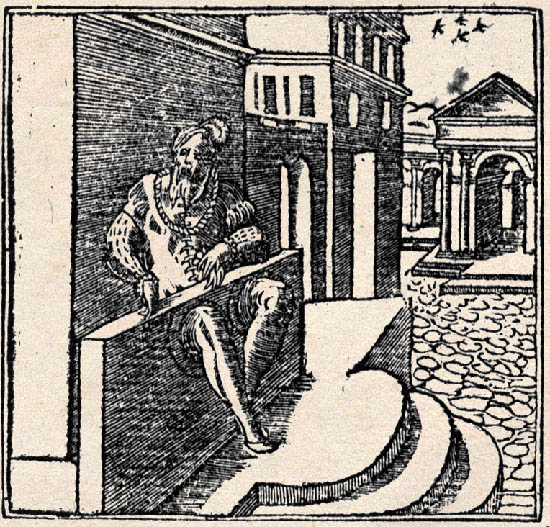

Hans Vredemann de Vries, Antwerpen Street View, with Hieronymus Cock’s publisher in the right corner, where this engraving was also printed in 1560, and with Hieronymus Cock himself in the door

Hans Vredemann de Vries, Antwerpen Street View, with Hieronymus Cock’s publisher in the right corner, where this engraving was also printed in 1560, and with Hieronymus Cock himself in the door

In the Antwerp art market, a promising young beginner might prevail by positioning himself as a master of the popular themes that had come to life in the previous decades. Until the early 1500s, there was one single marketable theme: the altarpiece, whether for the church or private. At the establishment of the art market and collections – Kunst- und Wunderkammer – in the 16th century, however, new themes appeared in which collectors specialized: landscapes, exotic topics, peasant scenes, and so on. Among the new themes, Bosch replicas were an independent sector. Bosch’s thrilling fantasy creatures were extremely popular, but his original paintings were mainly accumulated by Philip II of Spain for his private collection, and the market cried for substitutes. A lot of painters specialized in this, the production of copies after Bosch and new creations in his style. Among them was Bruegel, who made several drawings of Boschian monsters, and they were published in print by Cock for great profit.

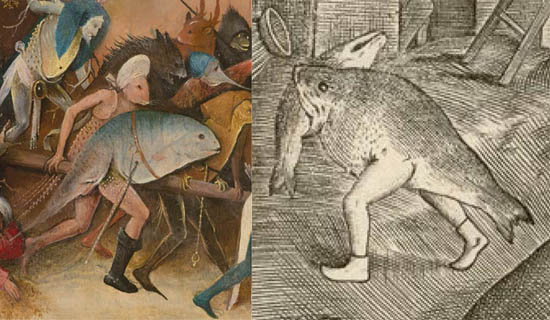

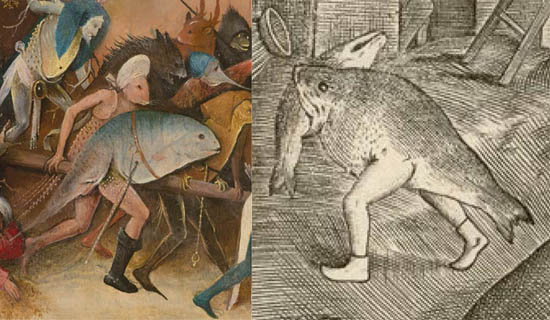

Bruegel, The temptation of St. Anthony, 1554. This scene was one of the main themes of the imitators of Bosch, because the demons tempting the holy hermit offered a generous pretext to the representation of Bosch’s typical monsters.

Bruegel, The temptation of St. Anthony, 1554. This scene was one of the main themes of the imitators of Bosch, because the demons tempting the holy hermit offered a generous pretext to the representation of Bosch’s typical monsters.

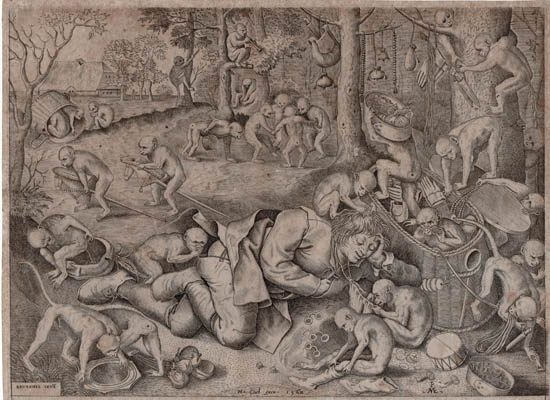

One of the most successful pieces of the collaboration of Bruegel and Cock was the series of prints representing the seven deadly sins, the seven virtues, and the Last Judgment, in 1557-60. The success was largely attributed to the Boschian

devileries, which flooded almost every sheet of the series: those of the sins naturally, but also those of the virtues, in the form of the demons defeated by them.

Bruegel, Ira (Anger), 1558

Bruegel, Ira (Anger), 1558

Bruegel, Fortitudo (Strength), 1560

Bruegel, Fortitudo (Strength), 1560

In 1572, the humanist

Dominicus Lampsonius from Bruges published at Cock’s a portrait collection of great Netherlandish artists. By that time, Bruegel’s reputation as a Bosch imitator was so great, that Lampsonius could write about him:

“He is the new Hieronymus Bosch, who with his brush imitates and sets in front of our eyes the clever dreams of the Master, and mimics his style so greatly, that at the same time he surpasses him.” From here comes the attribution of Bruegel as the “second Bosch”, which, thanks to the description of the Netherlands by Lodovico Guicciardini, was also spread through Southern Europe.

In the fish print of 1557, Bruegel did not yet use such typical Boschian monsters. But to the contemporary viewer, the fishes swallowing each other were already a trademark of Bosch, who often depicted his demons likewise. Interestingly, the motif is repeatedly featured in the film

Ruben Brandt, the collector (2018), which works with numerous references of art history and absurd images. If you have not seen it yet, do so (and if you have, watch it again) and count the fishes.

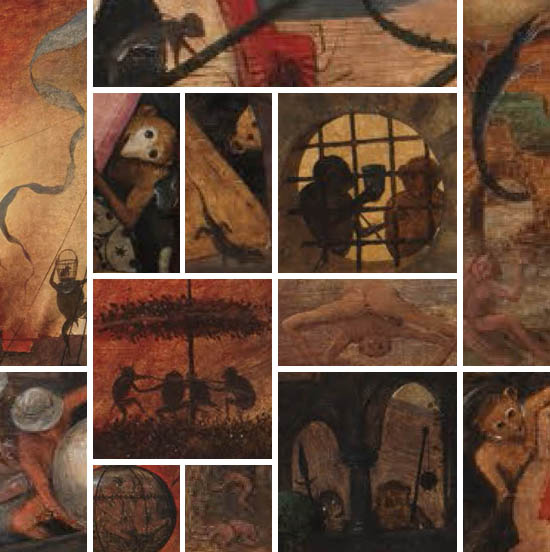

Bosch, The temptation of St. Anthony, c. 1501, detail

Bosch, The temptation of St. Anthony, c. 1501, detail

Bosch, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1485-1500, detail

Bosch, Adoration of the Magi, c. 1485-1500, detail

Bosch, The garden of earthly delights, c. 1490-1510, detail

Bosch, The garden of earthly delights, c. 1490-1510, detail

Bosch, The Haywain, 1516, detail. To the right, the fish on two legs from Bruegel’s fish print

Bosch, The Haywain, 1516, detail. To the right, the fish on two legs from Bruegel’s fish print

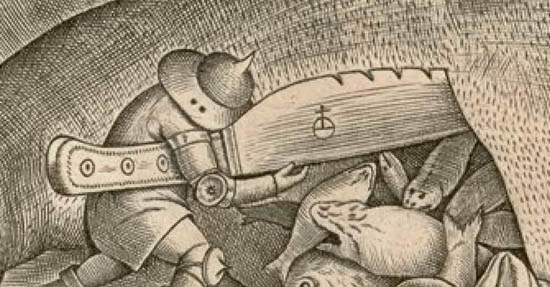

Bruegel, The Last Judgment, 1558, detail

Bruegel, The Last Judgment, 1558, detail

Milorad Krstić, Ruben Brandt, the collector, 2018. A detail of the episode about the Tokyo pop art exhibition

Milorad Krstić, Ruben Brandt, the collector, 2018. A detail of the episode about the Tokyo pop art exhibition

In 1556, when Bruegel drew and signed the model of the fish print, he was still an unknown young talent, who might have a future thanks to Cock (and Cock a profit thanks to Bruegel). Bosch, however, was a brand. Perhaps this is why Cock decided to name Bosch as the “inventor” of the print. At that time, this did not necessary mean deceiving the consumer. It was merely a genre: this is “a bosch”, or, in greater detail: “designed after Bosch by a fellow of our publisher”. And the consumer who bought it and kept it for at least fifteen years, by which time Bruegel had also become a brand, well, he could boast of having a bosch, that was actually a bruegel.

To illustrate the career of the picture among the consumers in the Netherlands, let us see this example sixty years later.

The facing page image shows that it was copied from Cock’s original print. However, the general social criticism is sharpened here into a political debate. The Fish bears the label “Barnevelsche Monster”, from which – and from other details – it can be inferred that the pamphlet celebrates the execution of

Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, the Chancellor of the United Provinces of the Netherlands in 1619.

Gilles-Lambert Godecharle: Johan van Oldebarnevelt (1549-1619), 1817. Brussel, Royal Museum of Fine Arts

Gilles-Lambert Godecharle: Johan van Oldebarnevelt (1549-1619), 1817. Brussel, Royal Museum of Fine Arts

The Chancellor, who had been the supreme judge of the Free Netherlands for thirty years, finally came into conflict with the States of the Netherlands as a supporter of the Arminian branch of Calvinism, and they convinced Governor-Prince Maurice of Nassau to condemn and execute him in a kangaroo court, just as in the print the Prince cuts open the stomach of the “monster” with “the knife of righteousness”. The “monster” is killed by the harpoon of the “Oude Leer”, that is, orthodox Calvinist teaching, and the city on the horizon rises up and gains independent features as Utrecht, Oldenbarnevelt’s last refuge. Posterity considers Oldenbarnevelt as a great statesman, but in the course of thirty years he may have injured some: their names can be read on the fishes slipping from its stomach and throat. Truth triumphed, from someone’s point of view. The question is – just as a big fish once asked a small fish before swallowing it –: what is truth?

Andrea Alciato also imagines the courtier in chains, with freely flying birds above him. Los emblemas de Alciato traducidos en rimas españolas, Lyon: Roville-Bonhomme, 1549, «In aulicos» (on courtiers), p. 146.

Andrea Alciato also imagines the courtier in chains, with freely flying birds above him. Los emblemas de Alciato traducidos en rimas españolas, Lyon: Roville-Bonhomme, 1549, «In aulicos» (on courtiers), p. 146.