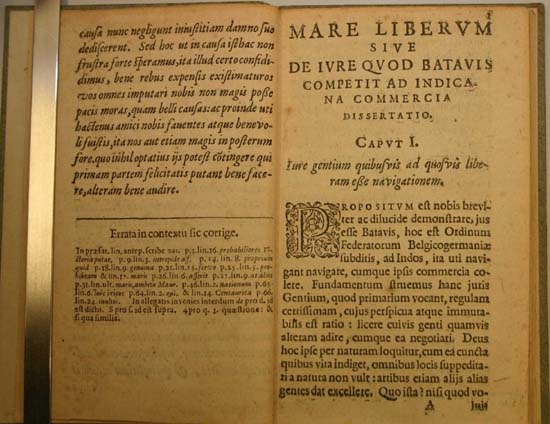

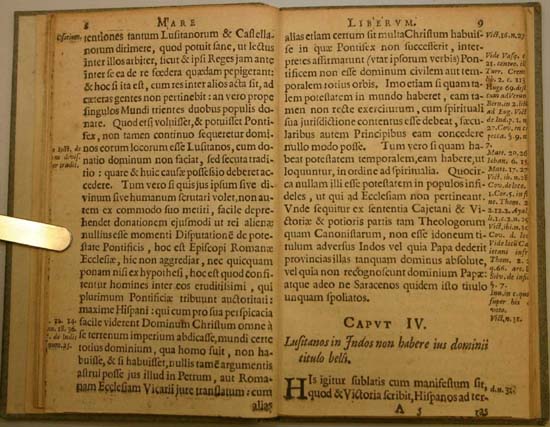

MARE LIBERUM

MARE LIBERUM

SIVE

DE IURE QUOD BATAVIS

COMPETIT AD INDICA-

NA COMMERCIA

DISSERTATIO

CAPUT I

Iure gentium quibusvis ad quosvis libe-

ram esse navigatione

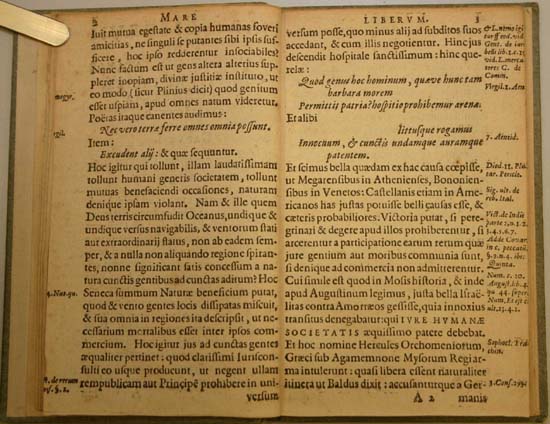

By the Law of Nations navigation is free to all persons whatsoever

My intention is to demonstrate briefly and clearly that the Dutch – that is to say, the subjects of the United Netherlands – have the right to sail to the East Indies, as they are now doing, and to engage in trade with the people there. I shall base my argument on the following most specific and unimpeachable axiom of the Law of Nations, called a primary rule or first principle, the spirit of which is self-evident and immutable, to wit: Every nation is free to travel to every other nation, and to trade with it.

God Himself says this speaking through the voice of nature; and inasmuch it is not His will to have nature supply every place with all the necessaries of life, He ordains that some nations excel in one art and others in another.

Why is this His will, except it be that He wished human friendships to be engendered by mutual needs and resources, lest individuals deeming themselves entirely sufficient unto themselves should for that very reason be rendered unsociable? So by the decree of divine justice it was brought about that one people should supply the needs of another, in order, as Pliny the Roman writer says, that in this way, whatever has been produced anywhere should seem to have been destined for all.

…

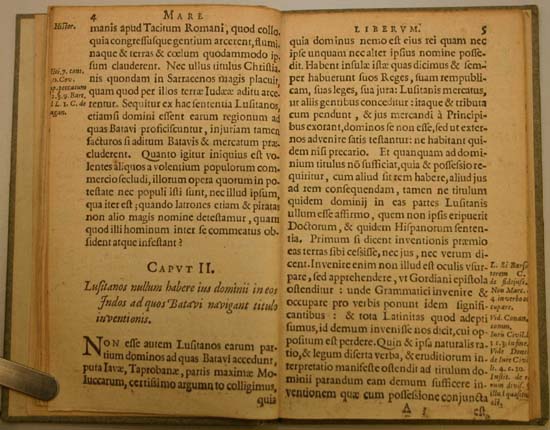

CAPUT II

Lusitanos nullum habere ius dominii in eos

Indos ad quos Batavi navigant

titulo inventionis

The Portuguese have no right by title of discovery to

sovereignty over the East Indies to which the

Dutch make voyages

The Portuguese are not sovereigns of those parts of the East Indies to which the Dutch sail, that is to say, Java, Ceylon, and many of the Moluccas. This I prove by the incontrovertible argument that no one is sovereign of a thing which he himself has never possessed, and which no one else has ever held in his name. These islands of which we speak, now have and always have had their own kings, their own government, their own laws, and their own legal systems. The inhabitants allow the Portuguese to trade with them, just as they allow other nations the same privilege. Therefore, inasmuch as the Portuguese pay tolls, and obtain leave to trade from the rulers there, they thereby give sufficient proof that they do not go there as sovereigns but as foreigners.

…

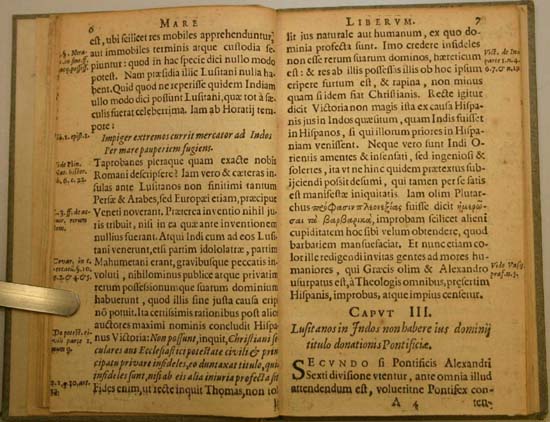

CAPUT III

Lusitanos in Indos non habere ius

dominii titulo donationis

Pontificiae

The Portuguese have no right of sovereignty over the

East Indies by virtue of title based on the Papal

Donation

Next, if the partition made by Pope Alexander VI is to be used by the Portuguese as authority for jurisdiction in the East Indies, then before all things else two points must be taken into consideration.

First, did the Pope merely desire to settle the disputes between the Portuguese and the Spaniards?

…

Second, did the Pope intend to give to two nations, each one third of the whole world?

…

(footnote by translator Magoffinat: “The Cambridge Modern History, I, 23-24, has a good paragraph upon this famous Papal Bull of May 14th, 1493 (modified June 7, 1494, by treaty of Tordesillas)”).

Not wanting to disrupt the solemn upbeat of this post, at this point we would like to greet and to recommend to the benevolence of the readers of Río Wang the new author of our blog Walter who introduces with this splendid essay his series presenting the secrets of his chosen homeland, the fabulous Singapore. (Studiolum)

|

Apologia

“Mare Liberum” or

“Mare Liberum, sive de iure quod Batavis competit ad indicana commercia dissertatio”, by Hugo Grotius (Hugo de Groot) 1583-1645, transcended its time and place to become the foundation for maritime law. Published in 1609 it derived from “

De Jure Praedae” of 1604, written for the

Dutch East India Company (VOC,

Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie) to justify the predations of the Dutch on Portuguese merchant vessels, in particular the capture of the Santa Catarina, a treasure-laden Portuguese carrack, at the eastern entrance to the Singapore Strait on February 25th 1603. The repercussions were immense. Were the Dutch acting legally as privateers or as pirates? Was the VOC a proxy for the Dutch States General in their struggle with Spain and thereby, through the joint crown, with Portugal?

We consider first the blurred boundaries between piracy, privateering and freebooting:

“…piracy, privateering (and the latter’s legal offshoot, freebooting) represent from the vantage point of European legal definitions quite distinct activities. Piracy is committed by private persons who have banded together and removed themselves from society at large and thus also from the protection of the law. Pirates were deemed enemies of the people and of the state. Privateering, by contrast, is a concept closely associated with the idea of the just war… Privateers operated under a so-called letter of marque and reprisal (Dutch: kaperbrief, commissie van retorsie), but they were technically only supposed to be issued with a letter of marque if they actually had suffered damage earlier by the enemy. The letter of marque, thus, permitted the seizure of goods from the (declared) enemy as a form of war reparation. This logic limited prizetaking to vessels sailing under enemy flag (or the flags of enemy allies) and only during times of war… This was how privateering was designed to work from a theoretical, legal vantage point. Actual practice was naturally quite different, and privateering effectively grew into a practice the full-blown proportions of which could have not been foreseen or anticipated in the late sixteenth or even the early seventeenth century…

The late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries–European privateers were authorized to seize commercial vessels of the (declared) enemy under direct and explicit instructions of their government, ruler or home port. A freebooter (from the Dutch: vrijbuiter; German: Freibeuter), a closely related term, was someone who may have captured a vessel authorized by a letter of marque, in an act of self-defence or reprisal and under the laws of war, but subsequently sold the captured goods on the open market without awaiting the verdict of the local admiralty court, declaring the seized vessel “good prize” and without also ceding to the home authorities their due share of the booty, the so-called gerechtigheit van het land. Failure to await the verdict and surrender this share – customarily 20 percent – to the home Admiralty Board technically rendered the act of prize-taking “illegal”, or at least highly problematic, from the vantage point of the home government. In other words, failure to abide by what in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries grew into a myriad of procedures and regulations edged an act of privateering into the shadow of piracy.

…traders who sailed under Spanish and Portuguese flags and also had become the victims of VOC privateering in the early seventeenth century often labelled the Dutch in Asia not only as “rebels” against their erstwhile overlord, the King of Spain, but also as thieves, hoodlums, bandits and of course as “pirates”.

With large prizes to be taken, it was not surprising that increasingly, letters of marque were issued after the event, irrespective of whether their captains had suffered damage, and with rapidly increasing trade, the problem was to escalate sharply in the latter part of the 17th century.

“…privateering practice led to the development of a particular type of sea robber, who, unlike the corsairs and merchant warriors of the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, was not committed to serve a single nation but operated on a ‘freelance’ basis for one sovereign after another, or for several at the same time… Unscrupulous sea robbers of this kind were so dangerous precisely because they always found the support of some nation or other, and were never the enemies of all nations at once.”

“

‘Even in the remotests corners of the world’. Globalized piracy and international law, 1500-1900”, Kemp (2010) (quoted by

Borschberg).

But are we in danger of projecting what is essentially a European legal framework onto the kingdoms of SouthEast Asia?

“The term ‘piracy’ was essentially a European one… The term subsequently criminalized political or commercial activities in Southeast Asia that indigenous maritime populations had hitherto considered part of their statecraft, cultural-ecological adaptation and social organisation… the dynamic interplay between raiding – merompak (Malay) or magooray (Iranun) – and investment in the maritime luxury goods trade that was a major feature of the political economies of coastal Malay states. In effect, maritime raiding was an extension of local-regional trade and competition, and a principal mechanism of state formation, tax collection and the processes for the in-gathering – forced and voluntary – and dispersion of populations in the late eighteenth century Southeast Asian world.”

“

A Tale of Two Centuries: The Globalisation of Maritime Raiding and Piracy in Southeast Asia at the end of the Eighteenth and Twentieth Centuries”, James Warren

The Maritime Silk Road

We turn to the event that led to the writing of

Mare Liberum propelling the young jurist Grotius to fame in the Councils of Europe (though he was later charged with treason, imprisonment and exile).

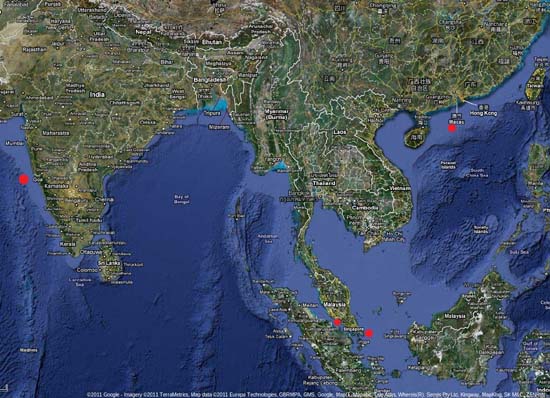

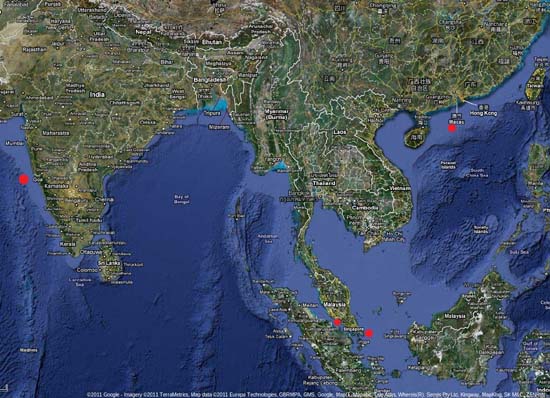

For much of the 16th Century, the Portuguese had expanded, under some secrecy, the rich China - Estado da Índia trade.

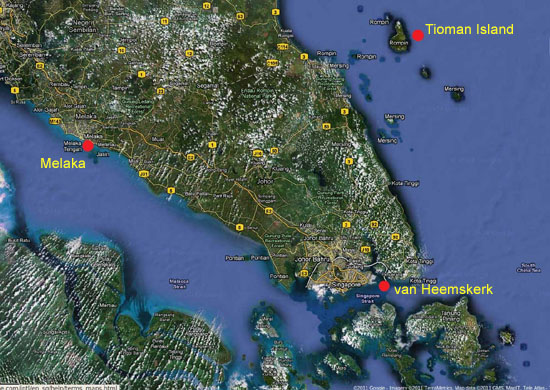

The Portuguese route between Macao and the Estado da Índia that passed through the Singapore and Malacca Straits to the trading port of

Melaka. Melaka (English,

Malacca) had been captured by

Afonso de Albuquerque from the Sultan Mahmud Shah in 1511, and was an important port to await the monsoon change, carry-out repairs and re-provision. The lightly-armed, heavily-laden Portuguese carracks, the bulk-carriers of the day, traveled in convoy, accompanied by Chinese junks, for the three week journey from Macao to Melaka.

Overview: Macao to Goa

Overview: Macao to GoaThe shortest route, through the Straits, was one of real danger, both from the local pirate invested waters of the Riau Archipelago, to the submerged shoals, sandbanks and fast currents of the Straits. Plotting a course was difficult and going aground an ever-present risk. The predation of local pirates had taken a more serious turn at the beginning of the 17th Century with the arrival of Dutch merchants and privateers. Diplomatic rivalry at the courts of Johor and Aceh was intense, and the Dutch newcomers tried hard to undermine the incumbents. Rivalry in trade is one thing, armed predation another.

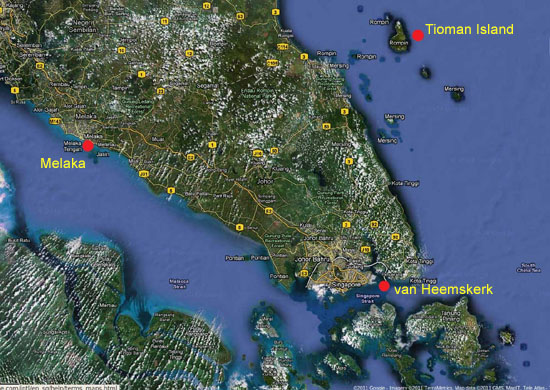

February 25th 1603: The Capture of the Santa Catarina

The Kingdom of Johor was in principle bound by Portuguese treaty, but the Dutch had also made strong representation, and the King’s half-brother, Raja Bongsu, was disposed to a Dutch alliance. It is likely that the Johoreans had been alerted to the Portuguese carracks as they took on fresh water at the island of Tioman, before the final run to Melaka.

Carracks at the end of the 16th century were large ships: the Santa Catarina was 1500 tonnes, drew 32 feet unladen, and was not very manoeuvrable. Passage through the straits would be too risky at night even at full moon, and in daylight would require an experienced pilot familiar with tides and landmarks. There was little margin for error: sudden squalls, then as now, could reduce visibility to nothing.

From Tioman Island to the Johor River – Setting the Trap

From Tioman Island to the Johor River – Setting the Trap

Perhaps tipped-off by the Johoreans, the much smaller ships, the

Witte Leeuw and the

Alkmaar of Admiral Jakob van Heemskerk, lay in wait off the Johor estuary. At dawn on February 25th 1603, van Heemskerk was told that a carrack of the Portuguese China fleet had been sighted at anchor. The

Witte Leeuw and the

Alkmaar engaged the Santa Catarina before it could flee, and for most of the daylight hours, cannon fire raked the sails and rigging of the Santa Catarina to disable her. It was a one-sided battle and before evening the Portuguese captain Sebastião Serrão, raised the white flag and offered to surrender his ship for safe passage for his crew and passengers to Melaka. Jakob van Heemskerk accepted the surrender and immediately took off some cargo as a precaution. European protocol prevailed, and in March, the Melaka Council thanked van Heemskerk for keeping his word, though they acidly pointed out that the Dutch were lucky to encounter this valuable vessel, and that it had fallen into their hands only through a ‘secret and unknown judgement of God’. The governor of Melaka, Dom Fernão de Albuquerque added that the carrack’s defense had been impeded by the many women and children on board, and had van Heemskerk met one of his own ships, the outcome would surely have been different. Truly a strange mix of warfare and formality!

The carrack’s contents were brought to Europe by the Dutch Admiral van Heemskerk. The return was not without incident, and one leaking ship had to be beached and used for repairs. With the delay, word had gone ahead of the rich prize and there was some apprehension that the English or French might try to take the prize in the Channel.

The Santa Catarina’s cargo became legendary:

“1,200 bales of raw Chinese silk; chests filled with coloured damask, atlas (a type of polished silk), tafettas and silk; large amounts of gold thread or spun gold; cloth woven with gold thread; robes and bed canopies spun with gold; silk bedcovers and bedspreads; linen and cotton cloth, thirty last (approximately sixty tonnes) of porcelain comprising dishes ‘of every sort and kind’; substantial quantities of sugar, spices, gum, musk (also known as bisem); wooden beds and boxes, some of them beautifully ornate with gold; and a ‘thousand other things, that are produced in China’” (Borschberg).

Merchants from all over Europe attended the auction in Amsterdam. The sale realised 3.5 million Guilders, half the capital-base of the VOC. Yet extraordinary as this was, the cargo was not unusual. No wonder the Dutch were determined to press their case for unfettered access to the East.

The Portuguese made representations through all the legal and diplomatic channels at their disposal. The young jurist Hugo de Groot (Grotius) was retained by the VOC and in short order prepared the case for the defense to which we have referred. The Dutch Admiralty Board ruled in favor of the VOC, marking the beginning of intense rivalry between the Dutch and Portuguese in the East Indies. Was van Heemskerk empowered to attack Portuguese merchant shipping, or was this privateering sanctioned after the event? Could only the States General could issue the letters of marque? Was the VOC a proxy for the States General in matters of war? The decision of the Dutch Admirality board we know, but the concept of Mare Liberum was certainly not agreeable to all, neither to the Portuguese nor to the English. What was clear, is that the auction of the Santa Catarina’s contents revealed the vast riches of China, and the virtual hegemony of the Portuguese in SE Asia was at an end.

(Peter Borschberg, a specialist in the Luso-Dutch conflict, has a scholarly yet readable

study of the Santa Catarina incident).

Four centuries later, the Singapore and Malacca Straits remain one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. Despite ships being almost head-to-tail day-and-night, with all the aids of modern navigation and armed security patrols, the region remains one of active piracy.

We will return to the region, but end this introduction with the moving request of Captain Sebastião Serrão, a casado of Goa, to Admiral Jakob van Heemskerk. Serrão had lost everything, was stranded far from home, and humbly requested Heemskerk to send him ‘a piece of felt’ ‘from which he could sew for himself new clothes’.

He would take this not only as a gesture of friendship, but as alms and in memory of the miserable condition in which he had been captured and later set free. (Borschberg).

We do not know if his request was answered. On 25th February 2011, we offer this post to the memory of Captain Sebastião Serrão.