![]() China, especially the western part, is full of small historic towns and villages. You will, however, look for them in vain in any Western-language guidebook. I don’t know what came first, the chicken or the egg: whether they aren’t in them because Western tourists don’t come to these hidden parts of China anyway, being satisfied with the Great Wall and the Xian Clay Army for those two weeks, or they don’t come because the guidebooks don’t talk about these parts.

China, especially the western part, is full of small historic towns and villages. You will, however, look for them in vain in any Western-language guidebook. I don’t know what came first, the chicken or the egg: whether they aren’t in them because Western tourists don’t come to these hidden parts of China anyway, being satisfied with the Great Wall and the Xian Clay Army for those two weeks, or they don’t come because the guidebooks don’t talk about these parts.

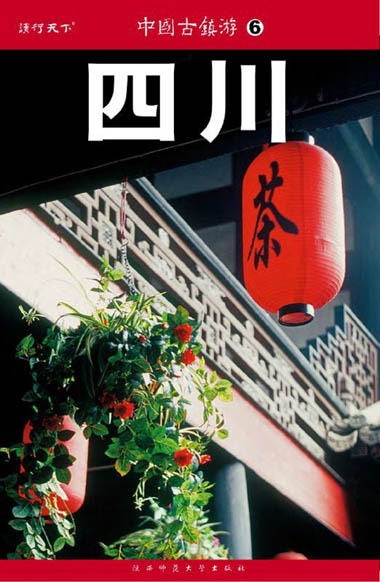

If you are curious about these small towns, you must read special Chinese guidebooks whose titles end in 古镇 gŭzhèn, “old town”. There are many such publications in China, because Chinese travelers with sophisticated tastes love and seek out these time capsules. When I wrote to the Chinese bus company the list of small towns I wanted to visit with my group in the mountains around Chengdu, they gave me the exact routes and times without blinking, just indicating that sometimes the bus will cover the thirty kilometers between two towns in an hour.

Such is the road, too, which leads to Wangyu, some two hundred kilometers south-west of Chengdu. From Ya’an, the starting point of the Sichuan branch of the tea and horse road, a steep and narrow two-lane road winds its way up into the mountains. A single oversized truck is able to block the road, turning with amazing maneuvers at every hairpin bend. The cars which otherwise rarely drive here, including our minibus, slowly gather into a long line behind it. Morning clouds are sitting on the mountains, the river is roaring in the depths. At longer stops, we get out to take photos. We cover the forty kilometers from Ya’an to Wangyu in two hours.

Next to us, it can already be seen that the patience of the province has run out, and they are building a four-lane road through the mountains. And Chinese road construction is a very spectacular undertaking. Concrete mixing facilities, valley bridges, tunnels and concrete road sections are everywhere. The construction is nearing completion. If it ends, the romance of the gŭzhèns of the highlands will probably end. My friend Shi Tan, a collector of Chinese folk music, said that you can only collect folk music in a Chinese village as long as no concrete road leads to it. We are doing this tour in the last hour.

Wangyu was built on the plateau of a high rock on the banks of Zhougong River. Not much before this, only a steep staircase of one hundred and fifty steps led up here from the river, but now, in connection with the road construction, a winding asphalt road has also been built, which reaches the village at the upper end. From there, slippery stairs lead down, then the path continues between barns and through vegetable gardens. However, at the upper end of the stairs, a modern road sign and a tourist reception center under construction indicate that the village will soon be integrated into the tourism industry.

From the path, you can see the roofs of the wooden houses and the courtyards along the main street. The village rests between the green mountains covered with clouds like in a cradle.

From the main street, you can see the river and the more modern houses built on the other bank. This is where the old town got its name: 望鱼 wàng yú means “watching the fish”. Local folklore holds the rock itself to be a curled-up cat watching the fish playing in the water before her nose.

But watching the fish is also a form or metaphor of meditation in the Chinese tradition.

According to a classic Taoist story, Chuangzi, while walking by a river, said to Hunzi: “See how the fish are playing and darting around as they please. That’s what fish really enjoy.” Huizi countered: “You are no fish. How do you know what the fish enjoy?” Chuangzi blurted out: “You are not me. How do you know I don’t know what fish enjoy?”

This epistemological debate is continued by the famous Song-era painter Zhou Dongqing in his six-meter-long scroll painting The Joy of Fish (1291, Metropolitan Museum of Art) on which he wrote the following poem next to the long row of playing fish:

| 非鱼岂知乐, 寓意写成图。 成探中庸奥, 分明有象无。 | | Being no fish, how can we know their joy? But we can express our own feeling in the picture. If we want to explore the depth of the ordinary, we must describe the indescribable. |

The path descends with steep steps to the main street, covered with stone slabs and lined with elegant wooden houses with columns and porches. The stone bases of the columns have 18th-century carvings. It can be seen that the village was rich sometime in the 17th and 18th centuries, when it was the main market for bamboo trade in the area. The wealth then passed, but the wooden houses, with their carved consoles and lintels, beautifully constructed windows and imposing internal structures have fortunately survived to this day. In 2013, Wangyu was awarded the title of “Sichuan’s most beautiful old village”.

One or two elderly people sit on the porches, offering tea or street food, and in one place, a group of people play cards. Today, the village has only sixteen permanent residents, but life is bubbling in the new village built at the foot of the cliff, many people come up from there, too.

In a gap between the houses, you can see mossy Taoist statues. In the small square between farm buildings are the remains of the village’s former sanctuary. Next to the two central statues – probably the ancestors who founded the village –, statues of gods sit on either side. Stepping behind them, the layers of time are revealed: a Buddhist statue of Guanyin, the Buddha of Mercy, next to it a small statue of Confucius, on the wall behind them a Communist pioneer scene in tiles, and behind that one, a modern construction sign on the recently built concrete retaining wall.

Continuing along the main street, a newly designed café cum bookshop displays a very nice example of the preservation and modern use of the old houses. The wooden façade and the internal column-and-beam structure with the roof structure have been preserved, but the internal spaces were opened up and connected with an accented wooden staircase. The emblem of the new building, a wooden frame standing on the head of a fish, refers to the name of the village and the essence of the building. The café sells the best Italian espresso and cappuccino, as well as Tibetan tea. The hipster furnishings and offering suggest that the village is frequented by an audience with refined tastes, and this will be even more so after the road is built.

The same audience is targeted, a little further away, by two houses opposite each other, run by a boy and a girl, maybe a couple, maybe brothers. They don’t look like locals, they may be university students who are here only for the shop. One of the houses, which are consciously kept in a rustic style, is a rustic café, and an excellent handmade clothing store is operated in the other. On the table in the clothing store is Hermann Hesse’s Glass Bead Game, in Chinese. The girl says she really likes this book, whose “spirituality” is very similar to Chinese spirituality. I felt the same when I read it thirty years ago.

A few houses after the double shop, the street ends with a lookout pavilion. The long staircase which until recently was the only way up to the village, leads down from here to the new town. Below the pavilion, you can see the roofs of this latter, as well as the concrete pillars of the new road under construction on the other bank of the river.

On the way back on the main street, we stop at a construction site, which shows how the café we just left has inspired the modern transformation of the old houses. The dividing walls and ceiling of the interior space have been removed, only the supporting columns and carved beams remain in place, and obviously some new wooden structure will be put up between them.

We continue towards the end of the main street, which must have been a less prestigious, more peasant, economical part of the village.

Two or three small local eating houses are open here, at least a hundred years old, as the well-worn Mao portrait and party slogans attest. Now the construction workers are having their lunch here.

The guidebook 四川古镇, Sichuan’s old small towns, which I bought thirty years ago in Beijing as a kind of pledge for the barely hoped-for opportunity to one day get to see these places, switches to a particularly lyrical tone when talking about Wangyu:

| 川北古镇中,望鱼是一个另类。想感受民风民俗,可以去元通;想欣赏特色建筑,可以去平乐;想了解历史人文,可以去街子。可是,想寻觅桃源,想慰藉心灵,想神游八荒,望鱼,就是赤子的彼岸。它地处半山腰,藏在深闺人未识,所以,它的破败也让人感动。它太小了,你有足够的时间来发现它细节的美;它太悠闲了,亲近它,谁都会乐不思返。 | | Among the old small towns of northern Sichuan, Wangyu is a special case. If you are interested in folk customs, go to Yuantong. If in specific architecture, go to Pingle. If you want a deeper understanding of history and culture, to Jiezi. But if you want to find paradise, to find your peace of mind, if you just want to wander about and watch the fish, then this is the place of innocence. Hidden among the mountains, in a secret chamber, unknown to everyone, it is striking even in its weariness. It is so small that you will have enough time to discover the beauty of its details, and so peaceful that once you immerse yourself in it, you will never want to leave it again. |

I wish it would stay that way.