I still have one hour until the train to Prague. I walk out in the town. Děčín – Tetschen – was a German spa town in the Bohemian/Saxon Switzerland until the deportation of the Sudeten Germans in 1946. This is still remembered by the Art Nouveau villas that decay in melancholy. Over the Elbe, on the edge of town rises

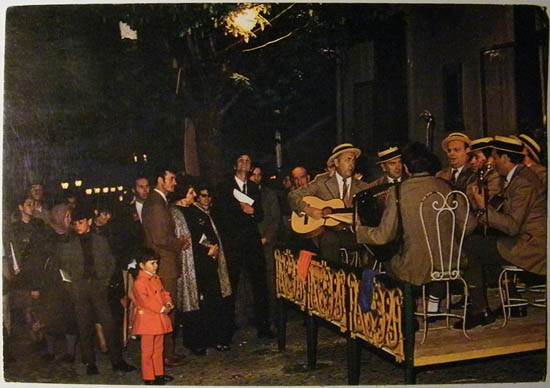

I still have one hour until the train to Prague. I walk out in the town. Děčín – Tetschen – was a German spa town in the Bohemian/Saxon Switzerland until the deportation of the Sudeten Germans in 1946. This is still remembered by the Art Nouveau villas that decay in melancholy. Over the Elbe, on the edge of town rises  the Tetschen Castle, founded in the 12th century, and then rebuilt in Renaissance and Baroque style. In 1808, Caspar David Friedrich painted his Tetschen Altarpiece (or Mountain Cross) for its chapel, where he for the first time elevated nature to the rank of religious painting, according to the creed of German Romanticism. The pines and the crucifix that rise on a lonely cliff fit very much to the castle rising on a sandstone cliff on the banks of the Elbe. And here Chopin wrote his “Valse brillante”, whose melancholic ebbs and flows coincide well with the atmosphere of the river pulsating beneath the castle and of the former small German town forgotten on the other bank.

the Tetschen Castle, founded in the 12th century, and then rebuilt in Renaissance and Baroque style. In 1808, Caspar David Friedrich painted his Tetschen Altarpiece (or Mountain Cross) for its chapel, where he for the first time elevated nature to the rank of religious painting, according to the creed of German Romanticism. The pines and the crucifix that rise on a lonely cliff fit very much to the castle rising on a sandstone cliff on the banks of the Elbe. And here Chopin wrote his “Valse brillante”, whose melancholic ebbs and flows coincide well with the atmosphere of the river pulsating beneath the castle and of the former small German town forgotten on the other bank.

Chopin: Valse brillante Op. 34. No. 2. a minor. Performed by Arthur Rubinstein

The sketch of the painting (1805-6), on the basis of which Countess Theresia von Thun-Hohenstein ordered the altarpiece

The sketch of the painting (1805-6), on the basis of which Countess Theresia von Thun-Hohenstein ordered the altarpiece There is an Art Nouveau restaurant on this side of the river, opposite the castle. It is also reminiscent of a lonely castle, and sometimes it was the first house of the city for a passenger coming from Germany. So it was probably the former customs house. This is indicated by the name of the restaurant – U Přístavu, To the Harbor, while there has been no harbor here for a long time –, but even more so by the carefully preserved Austrian imperial coat of arms on the corner of the building.

There is an Art Nouveau restaurant on this side of the river, opposite the castle. It is also reminiscent of a lonely castle, and sometimes it was the first house of the city for a passenger coming from Germany. So it was probably the former customs house. This is indicated by the name of the restaurant – U Přístavu, To the Harbor, while there has been no harbor here for a long time –, but even more so by the carefully preserved Austrian imperial coat of arms on the corner of the building.

The portrait of the emperor could be shat upon in rebellious Prague, the column of Mary, tied to the Habsburg power, pulled down by revolutionary vandals, but here, in the German Sudetenland, which was not so enthusiastic about the collapse of the Monarchy, the symbol of former unity was preserved. And now that nostalgia for the Monarchy is once again appreciating such relics, it has been nicely restored as well. So as for centuries before, now again it welcomes those coming from Germany to the territory of the former Monarchy. Welcome home.