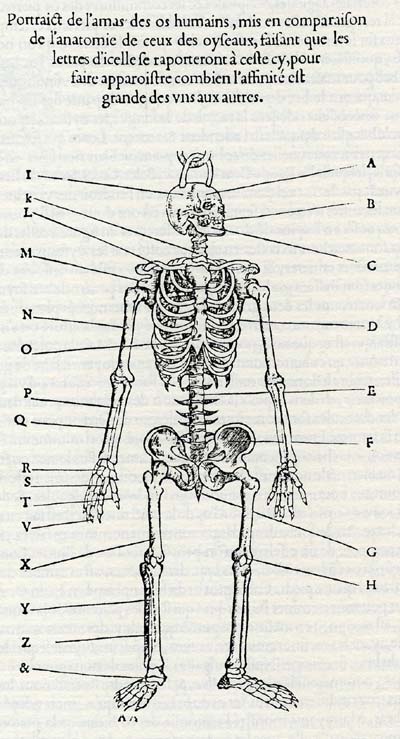

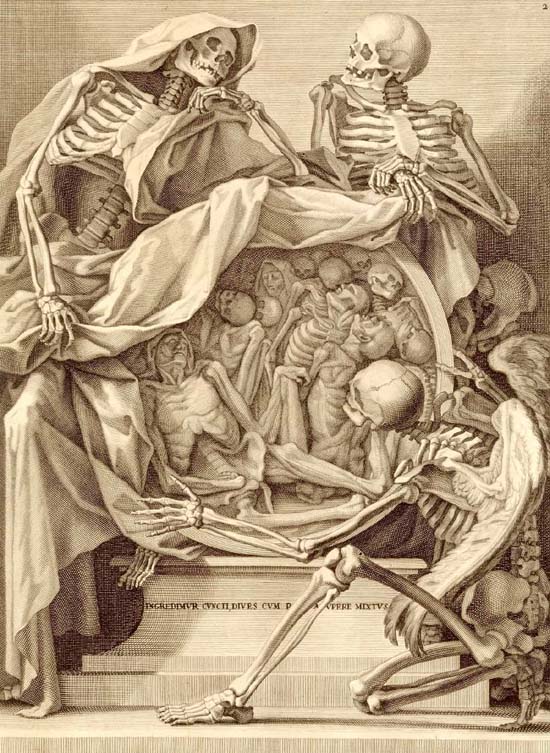

Human skeleton for comparison with that of birds. Pierre Belon, Nature des oyseaux (The nature of birds), Paris 1555

Human skeleton for comparison with that of birds. Pierre Belon, Nature des oyseaux (The nature of birds), Paris 1555An important motor of anatomical research was the Renaissance persuasion that things are explained by being reduced to their basic principles – in the case of anatomy, to their holding and operating framework. If the basic principles of two things are identical, the two things become comparable with each other. Without this persuasion, Linné’s taxonomy and Darwin’s evolution theory could have not been born two and three hundred years later, as they were in fact never born in China or in medieval Europe where no such relations were presupposed between races.

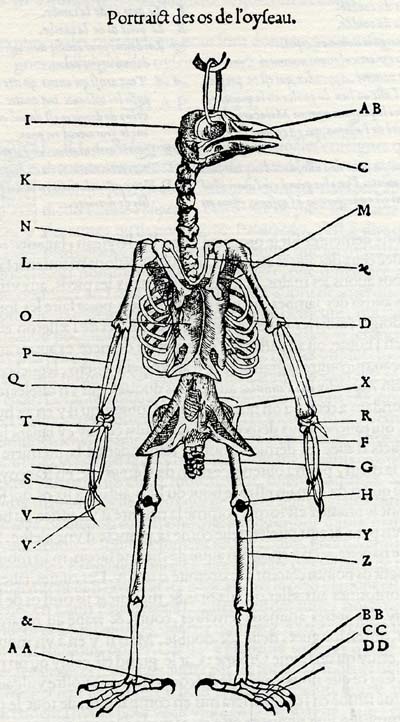

Counterpart of the previous image: Bird’s skeleton adjusted to the human anatomy for the purpose of comparison. Pierre Belon, Nature des oyseaux (The nature of birds), Paris 1555

Counterpart of the previous image: Bird’s skeleton adjusted to the human anatomy for the purpose of comparison. Pierre Belon, Nature des oyseaux (The nature of birds), Paris 1555In the natural histories of the 16th and 17th century this anatomical explanation and bringing to a common denominator of the old and new zoology went on at a good pace. Each recently discovered new animal or prodigious being became understandable and inserted in the common system for once as soon as its anatomy was described and, first of all, depicted.

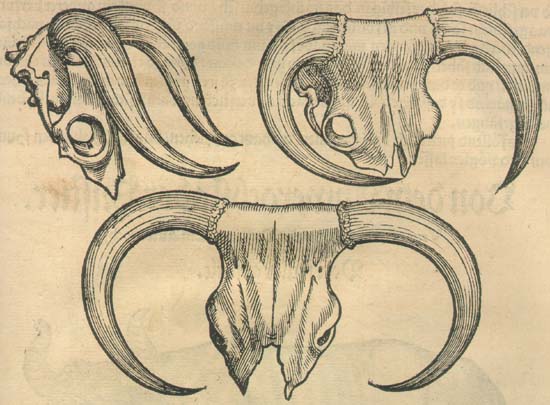

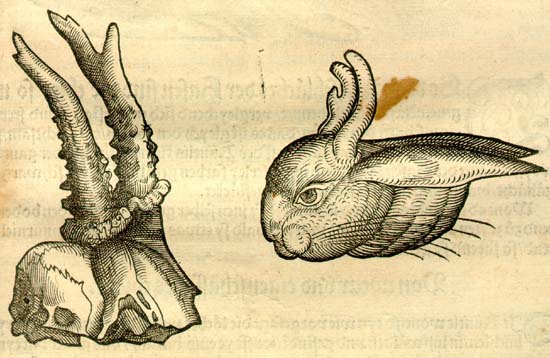

Comparison of exotic horn types and the anatomical explanatory design of the legendary animal known as “horned rabbit”. Conrad Gesner, Tierbuch, Frankfurt 1563

Comparison of exotic horn types and the anatomical explanatory design of the legendary animal known as “horned rabbit”. Conrad Gesner, Tierbuch, Frankfurt 1563

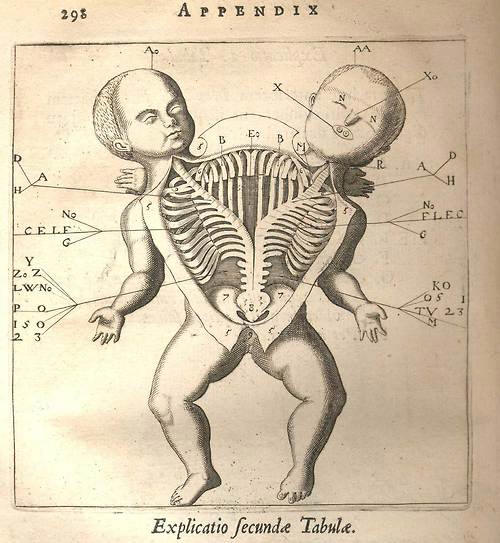

Anatomical drawing of a Siamese twin. Fortunio Liceti, De monstris, Amsterdam 1665

Anatomical drawing of a Siamese twin. Fortunio Liceti, De monstris, Amsterdam 1665The heroic age of biological taxonomy is long over, but anatomy as an explanatory principle is still able to take over with a special convincing force any wonderful being from the world of legends to our one.

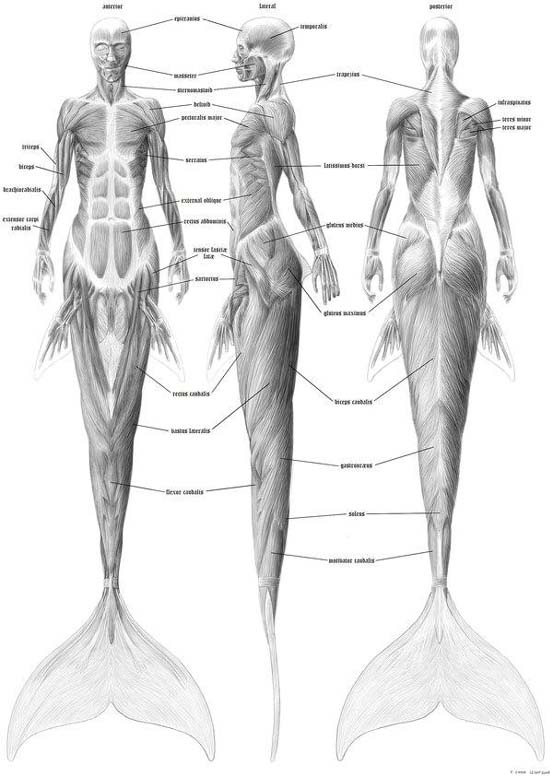

Skeleton and muscular system of a mermaid. According to the original caption, the “Hebrew

Skeleton and muscular system of a mermaid. According to the original caption, the “Hebrew script indicates this drawing is either based on another, much older work predating

Latin or Arabic anatomy texts, or merely a modern fabrication

attempting to imply antiquity or obscurity.”

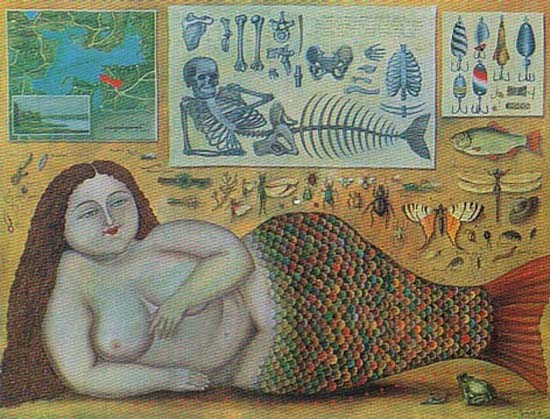

Valentin Gubarev (b. 1948): Common freshwater mermaid

Valentin Gubarev (b. 1948): Common freshwater mermaid

Edvard Eriksen (1876-1959): Little mermaid (1909-13), Copenhagen, and the “skeleton of an extinct mermaid” put on its place during its absence for the world expo of Shanghai

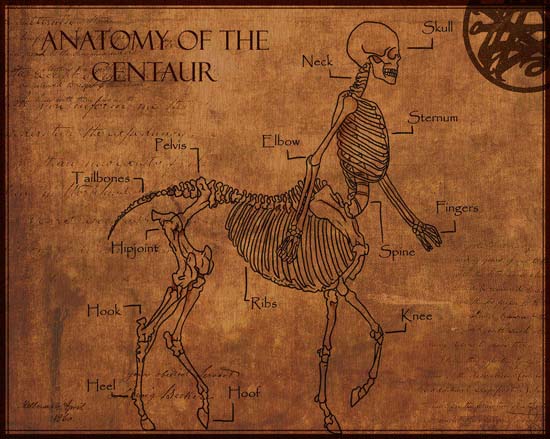

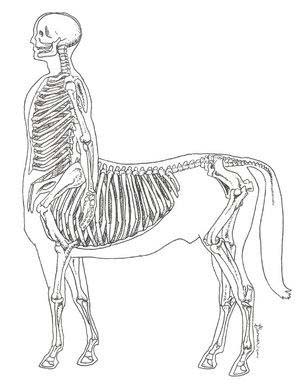

Edvard Eriksen (1876-1959): Little mermaid (1909-13), Copenhagen, and the “skeleton of an extinct mermaid” put on its place during its absence for the world expo of Shanghai Anatomy of a centaur. Double lungs and the presumably also double stomach gives

Anatomy of a centaur. Double lungs and the presumably also double stomach gives an explanation for the strength and perseverance of centaurs. In fact, Álvaro

Cunqueiro was wondering where they kept their navel.

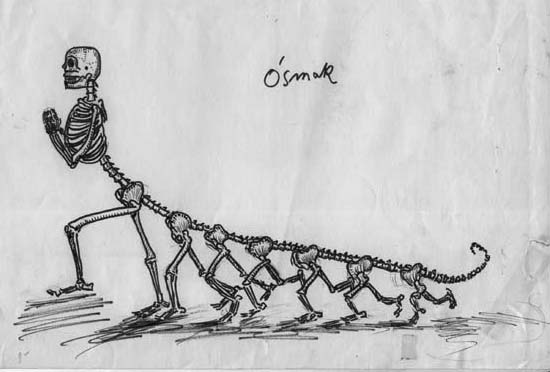

Stanisław Lem’s drawing: “Eight-point”. The Polish word “ósmak” refers to an eight-point

Stanisław Lem’s drawing: “Eight-point”. The Polish word “ósmak” refers to an eight-pointantler. Instead of the top of the body, the great science fiction author considered

its bottom as the point of departure of the “antler”, and created an

anatomically authentic version of the “eight points”.

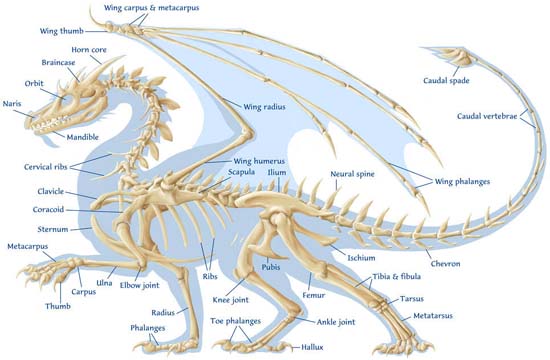

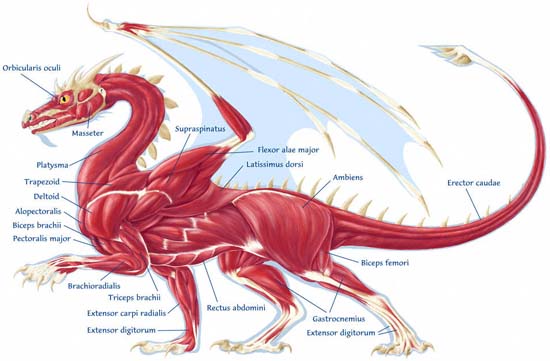

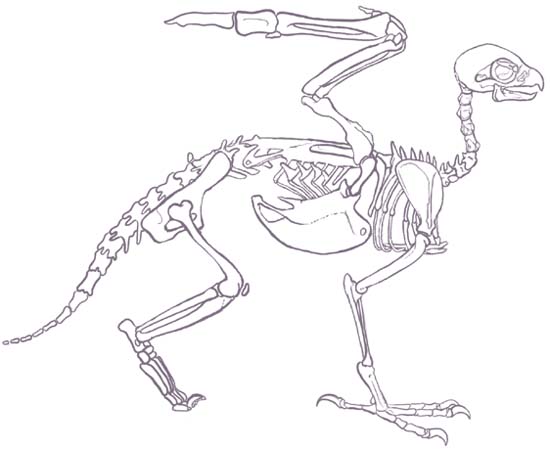

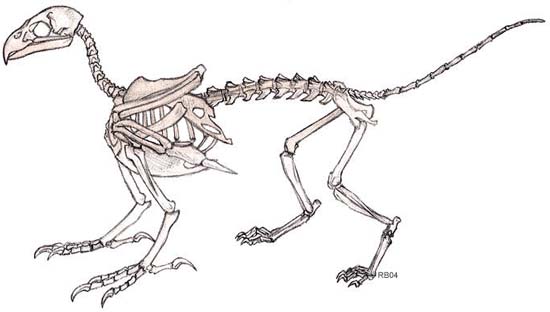

Dragons, as we know, are of two kinds. This is the skeleton and musculature of the Western dragon, widespread in Europe and in the Middle East (Eugene Arenhaus and Jennifer Walker).

Dragons, as we know, are of two kinds. This is the skeleton and musculature of the Western dragon, widespread in Europe and in the Middle East (Eugene Arenhaus and Jennifer Walker).

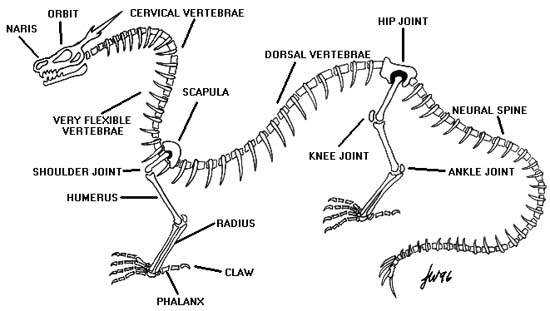

And this is the skeleton of the long, snake-like Eastern dragon native in China (Jennifer Walker).

And this is the skeleton of the long, snake-like Eastern dragon native in China (Jennifer Walker).

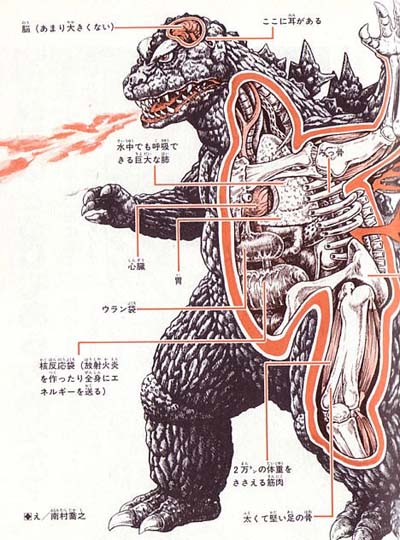

To Japan the fashion of anatomical drawings only came in the early 19th century – we will soon write about them –, but they were used for the demonstration of the structure and operation of legendary beings earlier than either in Europe or in America. The figures of the kaiju-cartoons were authenticated by a series of anatomical publications as early as the 1960s.

This anatomical sketch of Godzilla reveals a relatively small brain, giant lungs that allow

This anatomical sketch of Godzilla reveals a relatively small brain, giant lungs that allow underwater breathing, leg muscles that can support 20,000 tons of body weight,

and a “uranium sack” and “nuclear reaction sack” that produce

radioactive fire-breath and energize the body.

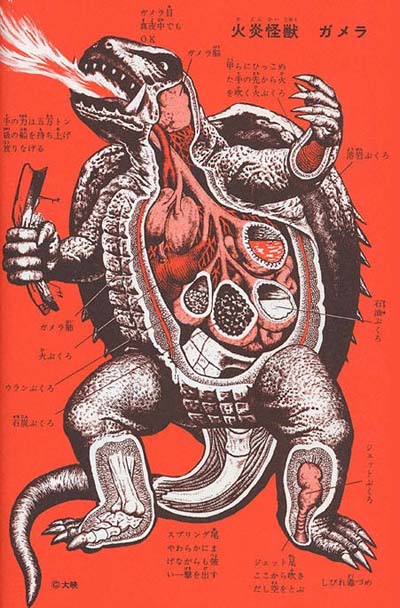

Gamera. The illustration also shows a series of sack-like organs for storing lava, oil, coal

Gamera. The illustration also shows a series of sack-like organs for storing lava, oil, coal and uranium (like Godzilla), as well as balloon-like organs in the legs

that can blast air through the bottoms of the feet.

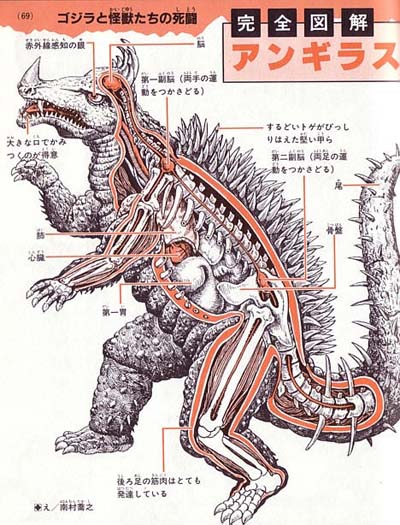

This anatomical diagram of Anguirus shows eyes that can detect infrared light, a pair

This anatomical diagram of Anguirus shows eyes that can detect infrared light, a pair of sub-brains that control the forelegs and rear legs, highly developed

rear leg muscles, and a heavily spiked rear carapace.

Recently Manga master Shigeru Mizuki has published a guide entitled Yokai Daizukai to the drawing of the yokai demons of traditional Japanese folklore, in which he, similarly to Western artist’s anatomies, has also put on display the anatomical diagrams of eighty-five demons, in this way grounding the special features attributed to them. The Pink Tentacle has published an English description of ten of them.

The Makura-gaeshi (“pillow-mover”) is a soul-stealing prankster known for moving pillows

The Makura-gaeshi (“pillow-mover”) is a soul-stealing prankster known for moving pillows around while people sleep. The creature is invisible to adults and can only be seen by

children. Anatomical features include an organ for storing souls stolen from

children, another for converting the souls to energy and supplying it to

the rest of the body, and a pouch containing magical sand that puts

people to sleep when it gets in the eyes. In addition, the monster

has two brains, one for devising pranks, and one for creating

rainbow-colored light that it emits through its eyes.

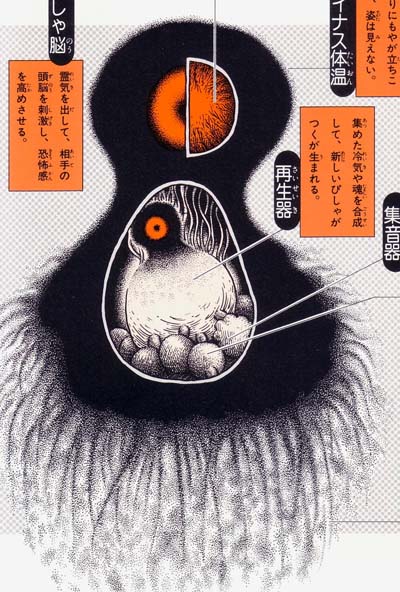

The Bisha-ga-tsuku is a soul-stealing creature encountered on dark snowy nights in northern

The Bisha-ga-tsuku is a soul-stealing creature encountered on dark snowy nights in northern Japan. The monster – which maintains a body temperature of -150 degrees Celsius – is

constantly hidden behind a fog of condensation, but its presence can be detected

by the characteristic wet, slushy sound (“bisha-bisha”) it makes. Anatomical

features include feelers that inhale human souls and cold air, a sac for

storing the sounds of beating human hearts, and a brain that emits a

fear-inducing aura. The Bisha-ga-tsuku reproduces by combining

the stolen human souls with the cold air it inhales.

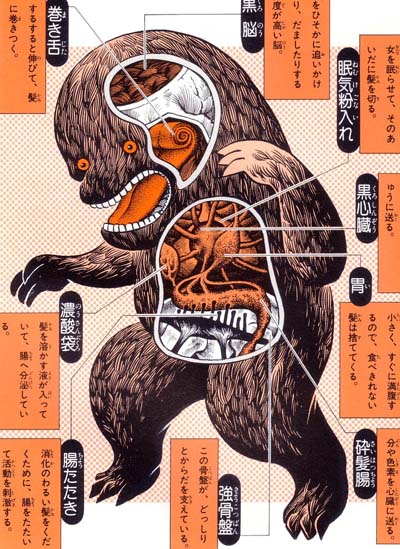

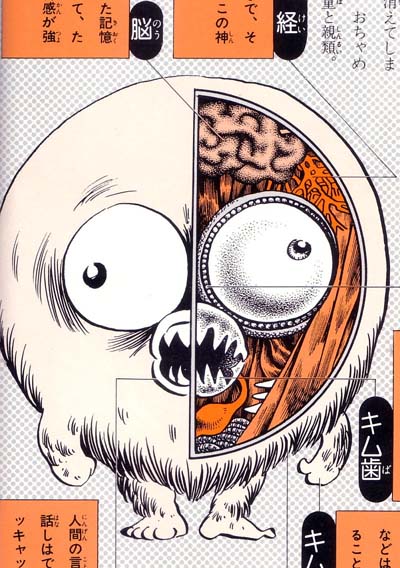

The Kuro-kamikiri (“black hair cutter”) is a large, black-haired creature that sneaks up on

The Kuro-kamikiri (“black hair cutter”) is a large, black-haired creature that sneaks up on women in the street at night and surreptitiously cuts off their hair. Anatomical features

include a brain wired for stealth and trickery, razor-sharp claws, a long, coiling

tongue covered in tiny hair-grabbing spines, and a sac for storing sleeping

powder used to knock out victims. The digestive system includes an

organ that produces a hair-dissolving fluid, as well as an organ

with finger-like projections that thump the sides of

the intestines to aid digestion.

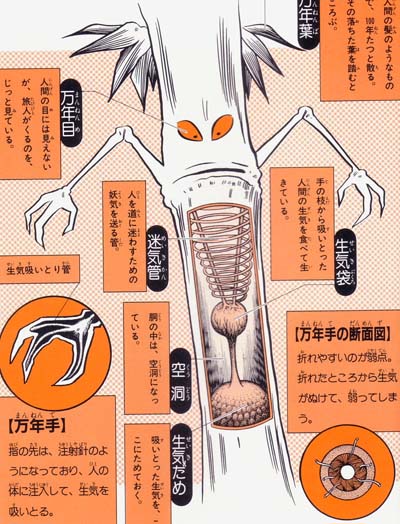

The Mannen-dake (“10,000-year bamboo”) is a bamboo-like monster that feeds on the souls of

The Mannen-dake (“10,000-year bamboo”) is a bamboo-like monster that feeds on the souls of lost travelers camping in the woods. Anatomical features include a series of tubes that

produce air that causes travelers to lose their way, syringe-like fingers the monster

inserts into victims to suck out their souls, and a sac that holds the stolen souls.

The Kijimunaa is a playful forest sprite inhabiting the tops of Okinawan banyan trees.

The Kijimunaa is a playful forest sprite inhabiting the tops of Okinawan banyan trees. Anatomical features include eye sockets equipped with ball bearings that enable

the eyeballs to spin freely, strong teeth for devouring crabs and ripping out

the eyeballs of fish (a favorite snack), a coat of fur made from tree

fibers, and a nervous system adapted for carrying out pranks.

The Kijimunaa’s brain contains vivid memories of

being captured by an octopus – the only

thing it fears and hates.

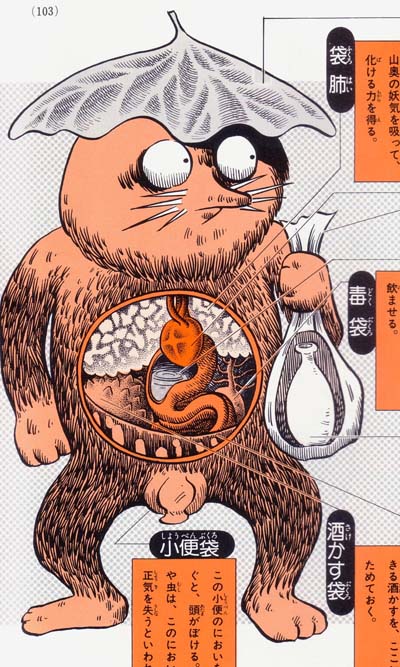

The Fukuro-sage – a type of tanuki (racoon dog) found in Nagano prefecture and Shikoku –

The Fukuro-sage – a type of tanuki (racoon dog) found in Nagano prefecture and Shikoku – has the ability to shapeshift into a sake bottle, which is typically seen rolling down

sloping streets. The bottle may pose a danger to people who try to follow it

downhill, as it may lead them off a cliff or into a ditch. Anatomical

features include a stomach that turns food into sake, and a sac

for storing poison that it mixes into drinks. The Fukuro-

sage’s urine has a powerful smell that can disorient

humans and render insects and small

animals unconscious.

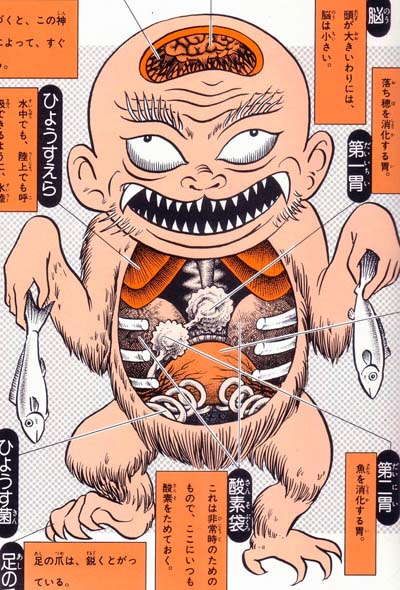

The Hyōsube, a child-sized river monster from Kyushu that lives in underwater caves,

The Hyōsube, a child-sized river monster from Kyushu that lives in underwater caves, ventures onto land at night to eat rice plants. The monster has a relatively small

brain, a nervous system specialized in detecting the presence of humans,

thick rubbery skin, sharp claws, two small stomachs (one for rice

grains and one for fish), a large sac for storing surplus food,

and two large oxygen sacs for emergency use. A pair

of rotating bone coils produce an illness-inducing

bacteria that the monster sprinkles

on unsuspecting humans.

Yanagi-baba (“willow witch”) is the spirit of 1,000-year-old willow tree. Anatomical features

Yanagi-baba (“willow witch”) is the spirit of 1,000-year-old willow tree. Anatomical features include long, green hair resembling leafy willow branches, wrinkled bark-like skin,

a stomach that supplies nourishment directly to the tree roots, and a sac for

storing tree sap. Although Yanagi-baba is relatively harmless, she is known

to harass passersby by snatching umbrellas into her hair, blowing

fog out through her nose, and spitting tree sap.

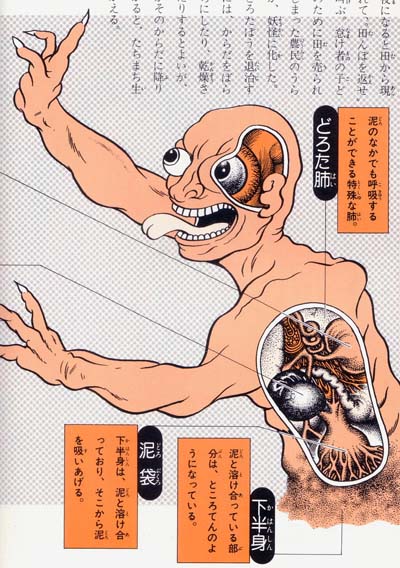

The Doro-ta-bō (“muddy rice field man”), a monster found in muddy rice fields, is said to be

The Doro-ta-bō (“muddy rice field man”), a monster found in muddy rice fields, is said to be the restless spirit of a hard-working farmer whose lazy son sold his land after he died. The

monster is often heard yelling, “Give me back my rice field!” Anatomical features include

a gelatinous lower body that merges into the earth, a ‘mud sac’ that draws nourishment

from the soil, lungs that allow the creature to breathe when buried, and an organ that

converts the Doro-ta-bō’s resentment into energy that heats up his muddy spit.

One eyeball remains hidden under the skin until the monster encounters the

owner of the rice field, at which time the eye emerges and

emits a strange, disorienting light.

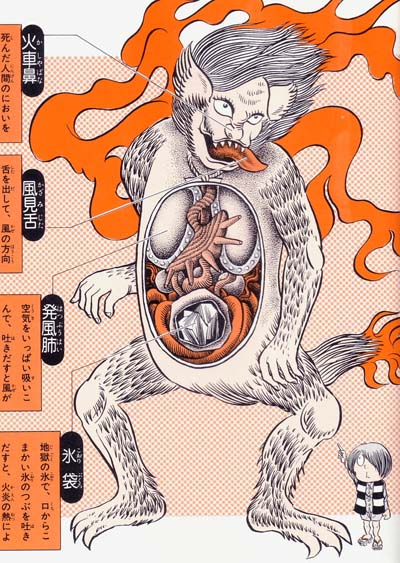

Kasha, a messenger of hell, is a fiery monster known for causing typhoons at funerals.

Kasha, a messenger of hell, is a fiery monster known for causing typhoons at funerals. Anatomical features include powerful lungs for generating typhoon-force winds that

can lift coffins and carry the deceased away, as well as a nose for sniffing

out funerals, a tongue that can detect wind direction, and a pouch

containing ice from hell. To create rain, the Kasha spits chunks

of this ice through its curtain of perpetual fire.

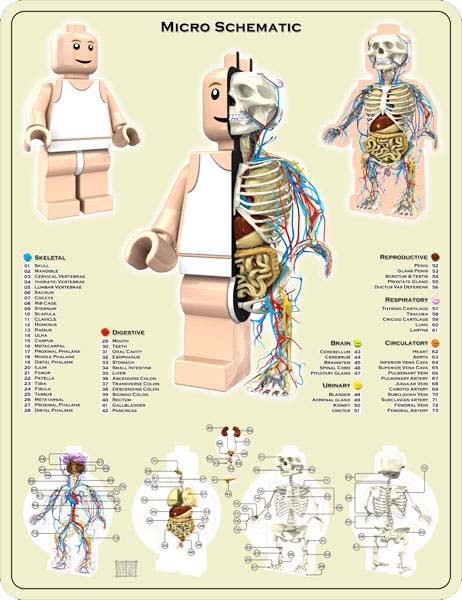

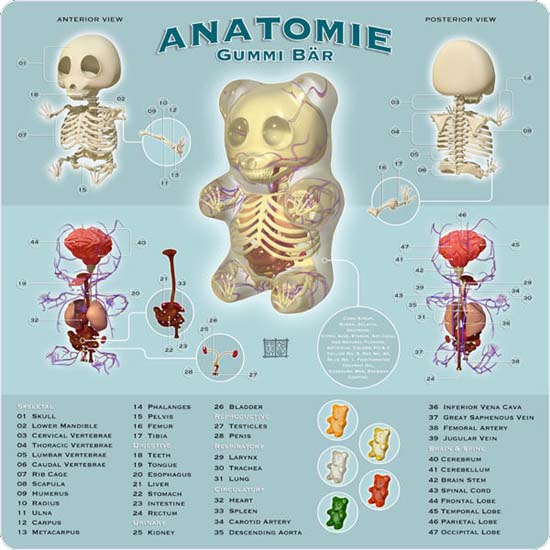

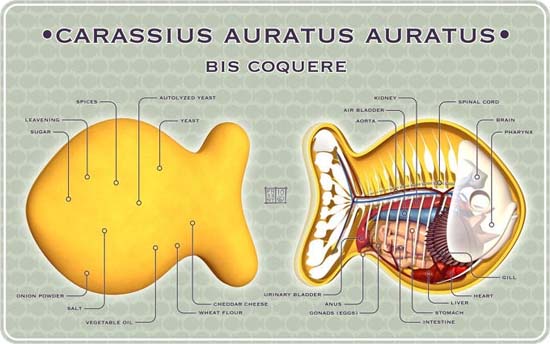

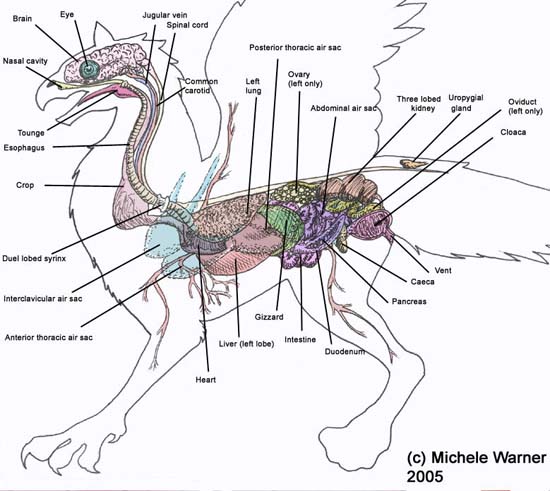

Finally, the most recent development of this method is the procedure by which Jason Freeny reveals the essential relationship of not just outwardly different living beings, but even of inanimate objects with us.

3 comentarios:

Fabulous. Very interesting, but I notice that not one of the creatures -- not even the centaur, who potentially has two sets -- has any sex organs. The Fukuro-sage kind of does, but he seems a bit young.

Anyway, just thought I'd mention it.

I’m not sure this is out of pure prudery. Skeletal and muscular diagrams do not have to include them, only the third layer demonstrating the operation of internal organs. And in the anatomy of the Lego Man, Gummibär and Hello Kitty (Felis Catus Salve) where this third layer is present, you can in fact see them. And as to the Japanese spirits where this layer is also represented, I’m not sure whether they as spirits have any reproductive organs (except for the Bisha-ga-tsuku where it is indicated).

No, you're right. Of course Gummibears have sex organs. I just wasn't wearing my glasses.

I think it's prudery in the case of the centaur -- either that or the artist couldn't decide which end to draw them.

Publicar un comentario