Tbilisi was literally born in a bath. Around 458, when King Vakhtang Gorgasali was hunting here on the banks of the Mtkvari/Kura, he saw a pheasant rise on the opposite side of the river and released his falcon. The falcon struck the pheasant, and both birds fell. Crossing the river, the king discovered them floating in a pool of hot water — already cooked. Taking this as a divine sign, he moved his seat of power here from his palace in Mtskheta, which he left as the center of the Georgian Church.

Today, the story is still vividly commemorated by the equestrian statue of King Vakhtang Gorgasali on the left bank of the river, on the hill of the Metekhi Church, just as he releases his falcon — and by the tiny statue of the pheasant, still gripped by the falcon even in death, on the opposite side, at the edge of a small pool. And of course, by the great, brick-domed, Persian-style thermal baths rising behind the bird statue.

The tale neatly sums up a much longer process. Hot sulphur baths already existed on the site of present-day Tbilisi in the 1st century BC. According to travelers such as Marco Polo and Ibn Hawqal, there were sixty-five of them in the 13th century. The many sieges of the city — Tbilisi was destroyed twenty-six times over fifteen hundred years — took their toll on the baths as well, but like the city itself, they were always rebuilt. Today, about a dozen still operate under the fortress, in Abanotubani, the old Muslim bath quarter on the edge of the former bazaar. After the Persian invasion of 1795, the aristocratic Orbeliani family rebuilt them in the Persian hammam style: square plans, brick domes with skylights, sunk deep into the ground so that the underground sulphur springs wouldn’t have to be pumped upward.

Soviet-era mosaic in one of Abanotubani’s Persian baths

Soviet-era mosaic in one of Abanotubani’s Persian baths

The baths were less about washing and much more about social life. This was where Tbilisians and foreign merchants met for family gatherings, business talks, and celebrations. Future mothers-in-law could discreetly inspect potential brides without veils. Travelers could even spend the night here before heading onward the next day.

That the baths were simply part of everyday life is shown by the fact that Georgian authors hardly wrote about them at all. Such things amaze foreigners, not locals. One of them was Alexandre Dumas, who visited Georgia in 1858 at the invitation of his Russian and Georgian aristocratic admirers. He recounts the journey in his hefty travelogue Le Caucase. Chapter XLI is dedicated to the Tbilisi baths, which made a strong impression on him. Since the book has never been completely translated into English, I quote the chapter below in my own translation.

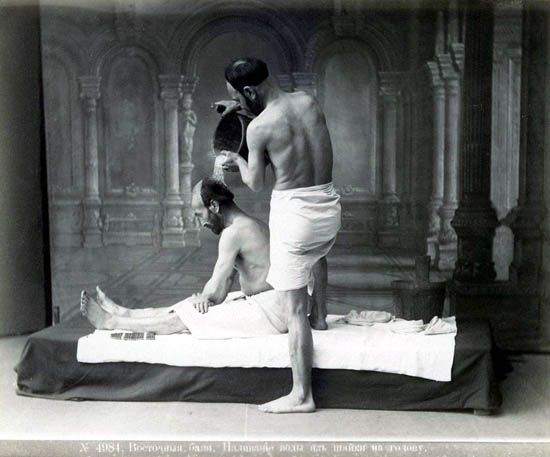

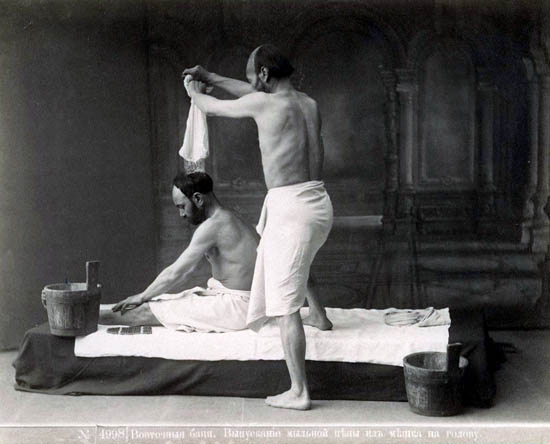

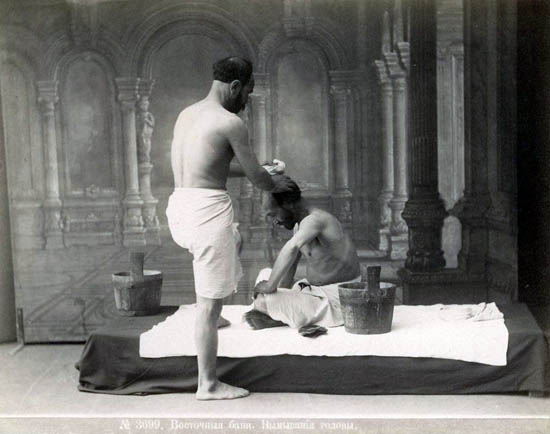

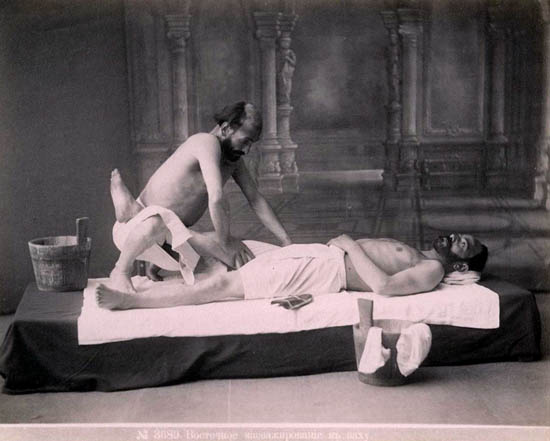

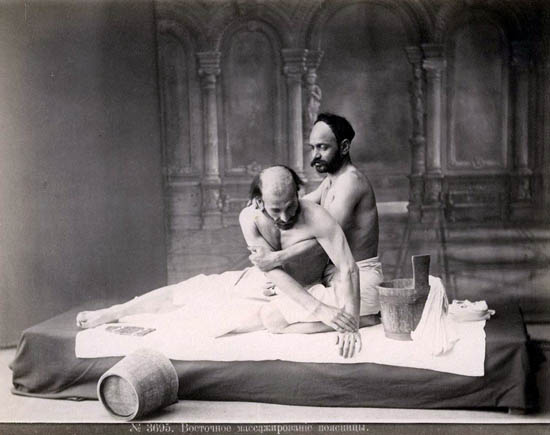

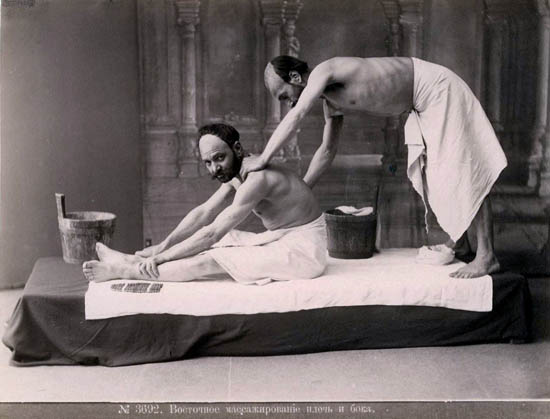

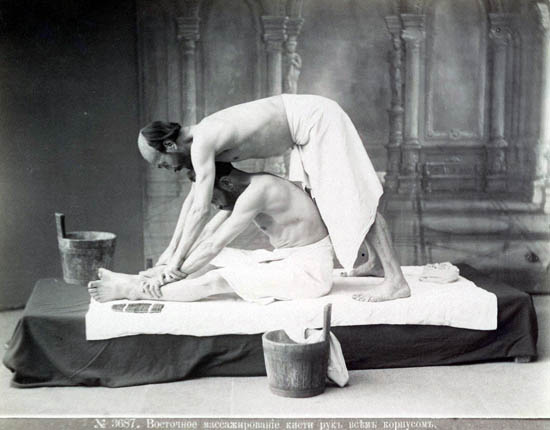

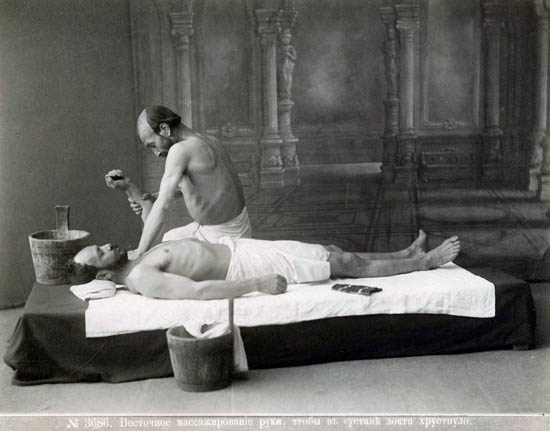

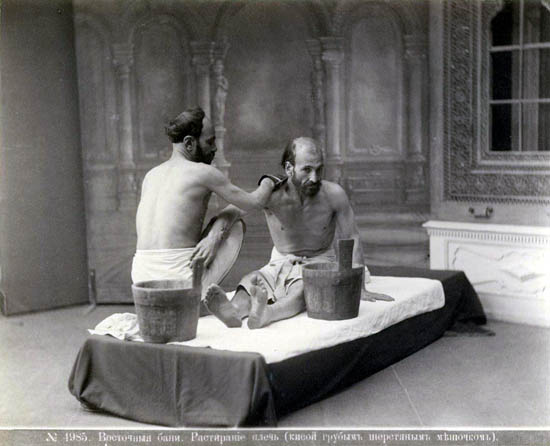

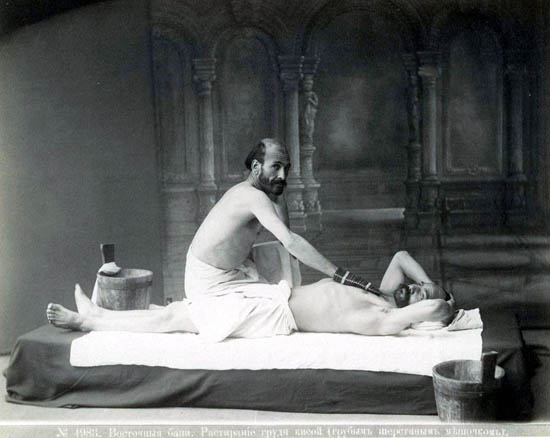

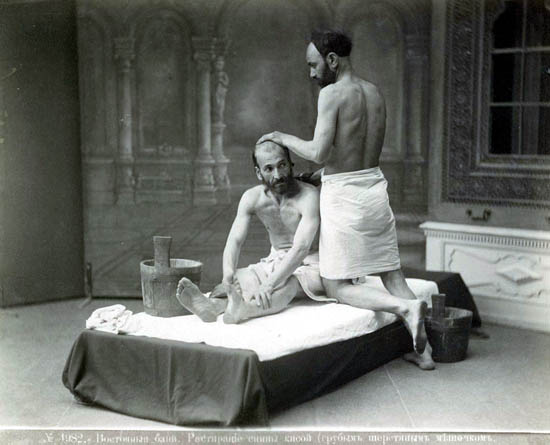

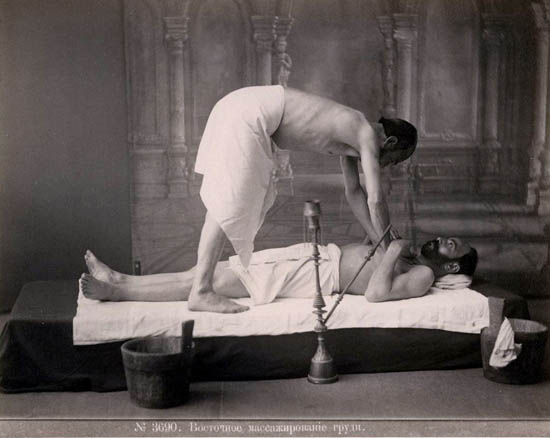

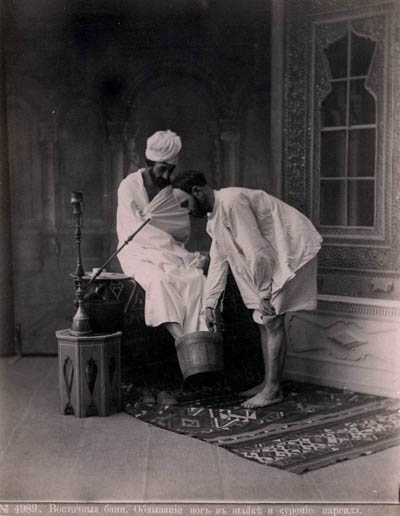

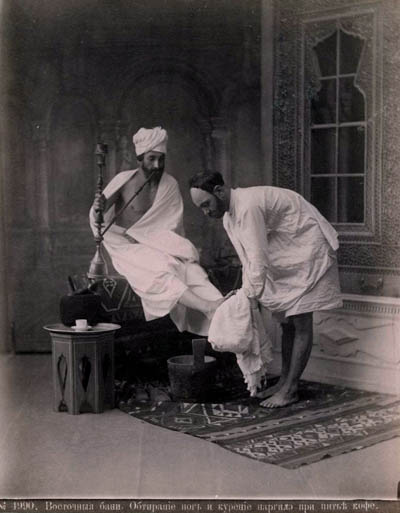

And although Dumas gives a wonderfully vivid description of the baths, we also have actual images from roughly the same period. Dmitri Ermakov, the early photographic chronicler of the Caucasus, took pictures here as well.

Ermakov’s archive of tens of thousands of photographs is released only sparingly by the Tbilisi State Museum. When I first wrote about him fifteen years ago, I included in the post all the images available at the time on Georgian and Russian websites. Since then, more have surfaced. Until recently, we knew only one photo of the traditional massage performed in the Tbilisi baths. Russian sites have now published an eighteen-image series of which that single photo was only one piece. The series shows that Ermakov wasn’t merely chasing exotic themes — although selling his photos as postcards was an important source of income — but was also documenting with anthropologist’s eyes a world whose approaching disappearance he already sensed.

Dumas starts his account with a solid foundation, mentioning that the name Tbilisi comes from the Georgian tbili, meaning "warm," and that its full original name was Tbili Khalaki, or "Warm Fortress." Interestingly, he adds, there’s also a spa town in Bohemia called Teplice, whose name likely derives from the Latin tepidus, meaning warm.

Dumas didn’t yet need to know about the Indo-European language family, which traces words like Teplice, тёплый, tepidus, and similar ones back to the Proto-Indo-European root *teplos—and which considers it purely coincidental that this resembles the Proto-Kartvelian root *t’bil, from which the Georgian tbili comes.

“One of the two bath attendants laid me down on a wooden bed, carefully placing a damp pillow under my head; then they stretched my legs together and aligned my arms along my sides. Then each of them grabbed one of my arms and started cracking my joints. The popping began at my shoulders and ended at the tips of my fingers. Next came the arms, then the legs. When my legs popped, they moved to my neck, then my vertebrae, and finally my lower back. This exercise, which could have seemed to risk total dislocation, happened quite naturally—not only without pain, but with a peculiar sense of pleasure. My joints, which had never uttered a word in their life, seemed to crack as if that had always been their way. I felt as if they could fold me up like a napkin and slip me between two shelves of a cabinet, and I would endure it silently.”

“After the first part of the massage was over, the two bathmen turned me over, and while one pulled my arms with all his strength, the other began dancing on my back, occasionally sliding his feet along my shoulder blades, then noisily landing them back on the board."

This man, who must have weighed around 120 pounds, strangely felt as light as a butterfly. He climbed onto my back, jumped off, then climbed back up, creating a chain of sensations that brought me into an incredible state of well-being. I breathed like never before; my muscles, instead of tiring, seemed to gain extraordinary strength—I would have bet I could lift the Caucasus with outstretched arms.”

“Then the two bath attendants started slapping my lower back, shoulders, sides, thighs, calves—and so on. I became like some musical instrument, on which they played a melody far more delightful to me than any aria from Guillaume Tell or Robert le Diable. And this melody had one big advantage over the two esteemed operas: I, who can’t sing a single verse of Malbrough without hitting a wrong note ten times, now followed the rhythm perfectly, nodding my head in time and never missing a beat. I was exactly in the state of a dreaming man, just awake enough to know he is dreaming, yet enjoying it so much that he makes every effort not to fully wake.”

“Finally, to my great regret, the massage ended, and they moved on to the last stage: soaping. One man slipped his hands under my arms and seated me on my behind, much like Harlequin would with Pierrot when he thinks he has killed him. Meanwhile, the other, wearing a glove, rubbed my entire body, while the first lad scooped buckets of 104°F water and poured them over my back and neck with full force. Suddenly the gloved man decided ordinary water wasn’t enough, pulled out a bag, and I watched it puff up, sweating a foamy lather that completely engulfed me. My eyes stung a bit, but I never felt anything sweeter than this foam cascading over my body.

How is it that Paris, the city of sensual delights, has no Persian baths? How has no entrepreneur brought two bath attendants from Tbilisi? Such a philanthropic act, and more importantly, a real fortune to be made.”

“Completely covered in the warm, milky-white, light, airy foam, I let them lead me to the pool, stepping in as if pulled by an irresistible force, as if nymphs who had abducted Hylas were there. All my companions were treated the same, but I was focused on myself. Only in the pool did I seem to wake up, reluctantly reconnecting with the outside world. We stayed about five minutes in the pools, then got out. Long, perfectly white sheets had been laid on the vestibule beds; the cold air surprised us at first, but gave a new, pleasant sensation. We sat on these beds, and pipes were brought to us.”

“I understand why smoking is typical in the East, where tobacco is a fragrance, and the smoke travels through perfumed water and amber pipes. But a clay pipe, or a fake Havana cigar, coming from Algeria or Belgium, chewed as much as smoked… ugh! There was a choice: kalyan, chibouk, and hookah, and each could be Turkish, Persian, or Indian as they pleased.

To complete the evening, one of the bath attendants brought out a type of one-legged guitar that rotates on its leg, so the strings seek the bow rather than the bow seeking the strings, and he played a plaintive melody to accompany verses by Saadi. This music rocked us so gently that our eyes closed, the kalyan, chibouk, and hookah slipped from our hands, and indeed, we fell asleep.”

Kayhan Kalhor: Improvisation in Shustari mode, kamanche solo, accompanied on tombak by Navid Afghah. Tehran, 2020

“During the six weeks I stayed in Tbilisi, I visited the Persian baths every other day.”

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario