I introduced the Jewish epilogue of the post on Saint Martin and his geese with this image, which, with its depiction of a goose-like bird and a signature unmistakably Jewish, proved perfect to illustrate the peculiar story of the Jews who delivered roast geese to the Habsburg emperor on Saint Martin’s Day.

But what exactly is this bird with that enormous egg?

The inscription only reads: זה עוף שקורין אותו בר יוכני zeh ʿof she-qorin oto Bar Yochnei, that is, “This is the bird called Bar Yochnei.”

All that remains is to figure out which bird is called Bar Yochnei.

1.

This name appears in the Babylonian Talmud. Tractate Bekhorot 57b amidst tales of wondrous animals and plants, mentions:

“Once an egg of the bird called bar yokhani (=the son of the nest) fell, and the contents of the egg drowned sixty cities and broke three hundred cedar trees.”

The colossal bird also shows up in Bava Batra 73b, in the adventures of Rabbah bar bar Hana whose travels and miraculous encounters would eventually find their way into Sinbad-style tales:

Once we were traveling in a ship and we saw a certain bird that was standing with water up to its ankles [kartzuleih] and its head was in the sky. And we said to ourselves that there is no deep water here, and we wanted to go down to cool ourselves off. And a Divine Voice emerged and said to us: Do not go down here, as the ax of a carpenter fell into it seven years ago and it has still not reached the bottom. […] Rav Ashi said: And that bird is called ziz sadai, as it is written: “I know all the fowls of the mountains; and the ziz sadai is Mine” (Psalms 50:11).

The mere existence of such a bird is miraculous enough—but two of them? That would be an even greater miracle. Later Talmudic commentators—implicitly the medieval Yalkut Shimoni, explicitly the Maharsha (1555–1631) of Poland in his commentary on Bekhorot 57b—identified the two as one and the same.

2.

We have thus learned that Bar Yochnei and the ziz sadai are one and the same. But what is the ziz sadai?

We’re in slightly better shape here: the ziz sadai is mentioned in two psalms. However, it doesn’t appear anywhere else in Scripture. Only the context of Psalm 50:10–11 hints at its identity:

כִּי־לִ֥י כָל־חַיְתֹו־יָ֑עַר בְּ֝הֵמֹ֗ות בְּהַרְרֵי־אָֽלֶף׃

יָ֭דַעְתִּי כָּל־ע֣וֹף הָרִ֑ים וְזִ֥יז שָׂ֝דַ֗י עִמָּדִֽי׃

Ki-lī kol-ḥaytō-yā‘ar, behēmōt beharᵉrê-’ālef.

Yāda‘tī kol-‘ōf hārīm, ve zīz sāday ‘immādī.

The difficulty is precisely that these two lines are translated in various ways, depending on how one interprets the animals behēmōt and zīz sāday mentioned in them.

for every animal of the forest is mine, and the cattle on a thousand hills.

I know every bird in the mountains, and the insects in the fields are mine.

(New International Version)

for all forest creatures are mine already, as are the animals on a thousand hills;

I know all the birds in the mountains; whatever moves in the fields is mine.

(Complete Jewish Bible)

A literal translation, preserving the parts with no clear interpretation, would read:

For the forest and all its beasts are mine, the Behemoth on a thousand hills;

I know every bird of the heavens, and the ziz sadai is mine.

The translation of Ziz Sadai as “field insect” or “thing that moves on the field” goes back to the highly respected 11th-century Rashi, who derived ziz from the verb zuz, meaning “to move about.” However, most early commentators of the Babylonian Talmud, who were still immersed in the original context, understood it as a bird—indeed, a giant bird. They reasoned that the two lines, each containing a hapax legomenon, confirm each other as referring to two distinct mythical creatures, and that Adonai here is glorifying Himself as the master of both. Just as He cites the third, Leviathan, in Job (40:25–32) as proof of His grandeur, as we have already seen:

„Can you catch the Leviathan with a hook or make a covenant with it to be your servant forever?”

Thus, the three creatures—Behemoth, Leviathan, and the ziz sadai—form a coherent triad. They are three gigantic, wondrous beings, far beyond human dimensions, yet Adonai maintains dominion over them. According to Talmudic commentators, Behemoth is the wonder of the land, Leviathan the wonder of the sea, and Ziz Sadai the wonder of the air, as it is a colossal bird.

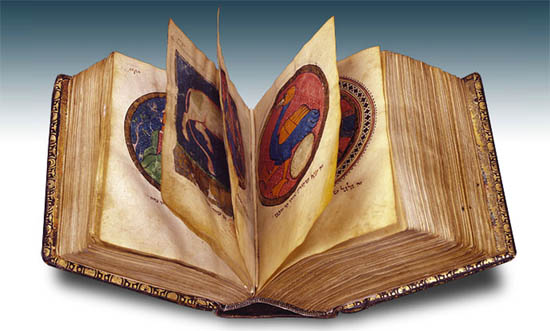

Behemoth, Leviathan, and the ziz sadai in the Ulm Hebrew Bible (1236-1238) of the Bibliotheca Ambrosiana

Behemoth, Leviathan, and the ziz sadai in the Ulm Hebrew Bible (1236-1238) of the Bibliotheca Ambrosiana

As for Leviathan, we have already noted that it originates from ancient Near Eastern creation myths, well known to the Jews living in Babylonian exile, and woven into their own mythology. During the Second Temple period, the strict priestly editors purged these myths from the Torah in its officially compiled form, yet traces remained in poetic or anecdotal texts, such as the Psalms or the Book of Job.

The central theme of these creation narratives is that the god or gods—Elil, or later Marduk, who replaced him—must first subdue chaos and its rebellious rulers, primarily in the waters, but also on land and in the air.

The so-called ʻAin Samiya goblet (c. 2300-2000 BC, found near Ramallah, now in the Israel Museum of Jerusalem) provides the earliest known depiction of the creation story. The god, having conquered chaos, sets the sun afloat on heavenly waters in a boat. Below, the so-called Lidar Höyük prism (c. 1800 BC) shows similar sun-launching scenes, demonstrating that this myth was widely known throughout the ancient Near East. All of this is discussed in the latest issue of Smithsonian magazine, 13 November 2025

The so-called ʻAin Samiya goblet (c. 2300-2000 BC, found near Ramallah, now in the Israel Museum of Jerusalem) provides the earliest known depiction of the creation story. The god, having conquered chaos, sets the sun afloat on heavenly waters in a boat. Below, the so-called Lidar Höyük prism (c. 1800 BC) shows similar sun-launching scenes, demonstrating that this myth was widely known throughout the ancient Near East. All of this is discussed in the latest issue of Smithsonian magazine, 13 November 2025

In the waters: Tiamat–Leviathan; on the land: the divine bull, which even Gilgamesh must confront; and in the air? There Anzu (by its original Sumerian/Akkadian name, Imdugud), the lion-headed giant bird of the mountains, who, according to the oldest surviving Akkadian myth, steals Enlil’s Tablet of Destiny—which grants its owner power over the fate of all living beings—and must be defeated by Enlil’s son, Ninurta. Here too, the forces of chaos rise against the new world order, and the gods must overcome them.

All of this is explored in detail by Nini Wazana of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in “Anzu and Ziz: Great Mythical Birds in Ancient Near Eastern, Biblical, and Rabbinic Traditions” Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society 31 (2009).

Anzu/Imdugud on the votive tablet of Entemena, ruler of Lagash, c. 2400 BC, Louvre

Anzu/Imdugud on the votive tablet of Entemena, ruler of Lagash, c. 2400 BC, Louvre

Anzu/Imdugud with two ibexes on a seal from c. 2154–2100 BC, Morgan Library & Museum

Anzu/Imdugud with two ibexes on a seal from c. 2154–2100 BC, Morgan Library & Museum

Anzu/Imdugud with two stags on the copper frieze from Tell-el-Obed, c. 2500 BC, former temple of Ninhursag, British Museum

Anzu/Imdugud with two stags on the copper frieze from Tell-el-Obed, c. 2500 BC, former temple of Ninhursag, British Museum

Anzu/Imdugud on a votive relief of King Ur-Nanshe of Lagash, from the ancient city of Girsu, c. 2550–2500 BC, Louvre

Anzu/Imdugud on a votive relief of King Ur-Nanshe of Lagash, from the ancient city of Girsu, c. 2550–2500 BC, Louvre

Anzu/Imdugud attacking a bull (possibly symbolizing the waning moon), from Tell-el-Obed, c. 2600–2500 BC, Penn Museum, Philadelphia

Anzu/Imdugud attacking a bull (possibly symbolizing the waning moon), from Tell-el-Obed, c. 2600–2500 BC, Penn Museum, Philadelphia

Anzu/Imdugud pendant in lapis lazuli and gold, from the so-called “Ur Treasure” discovered in the former royal palace of Mari (presumably a gift from the King of Ur to the ruler of Mari), c. 2500 BC, Damascus, Syrian National Museum

Anzu/Imdugud pendant in lapis lazuli and gold, from the so-called “Ur Treasure” discovered in the former royal palace of Mari (presumably a gift from the King of Ur to the ruler of Mari), c. 2500 BC, Damascus, Syrian National Museum

Anzu/Imdugud from the Tell Asmar Hoard, ancient Eshnunna, Baghdad, Iraq Museum

Anzu/Imdugud from the Tell Asmar Hoard, ancient Eshnunna, Baghdad, Iraq Museum

Anzu/Imdugud on the mace of King Mesilim Kishi dedicated to the god Ningursu, from ancient Girsu, c. 2600–2500 BC, British Museum

Anzu/Imdugud on the mace of King Mesilim Kishi dedicated to the god Ningursu, from ancient Girsu, c. 2600–2500 BC, British Museum

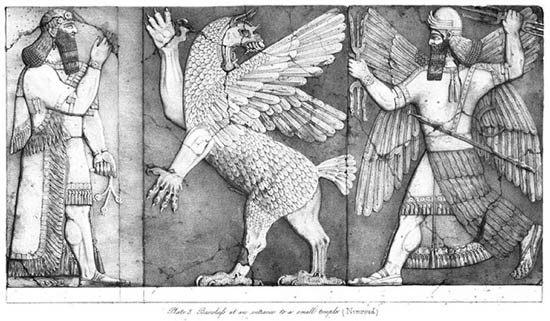

The struggle of Ninurta and Anzu on the entrance relief of an Assyrian temple in Nimrud, now in the British Museum. Engraving by Ludwig Gruner from Austen Henry Layard’s Monuments of Nineveh, 1853. A detailed description of the relief is available here

The struggle of Ninurta and Anzu on the entrance relief of an Assyrian temple in Nimrud, now in the British Museum. Engraving by Ludwig Gruner from Austen Henry Layard’s Monuments of Nineveh, 1853. A detailed description of the relief is available here

Ninurta attacking Anzu. Neo-Assyrian seal from Nimrud, 8th–7th century BC, The Walters Art Museum

Ninurta attacking Anzu. Neo-Assyrian seal from Nimrud, 8th–7th century BC, The Walters Art Museum

The so-called Adda Seal, c. 2300 BC: Anzu/Imdugud before the divine tribunal, British Museum

The so-called Adda Seal, c. 2300 BC: Anzu/Imdugud before the divine tribunal, British Museum

That Anzu indeed made it into the psalm, surviving there for three thousand years under the name ziz sadai, is further confirmed by the fact that the word saday—a hapax legomenon appearing only here in the Bible, with an uncertain meaning—derives from Anzu/Imdugud’s original Akkadian epithet šadû, meaning “mountain.” For Mesopotamia, mountains were the threatening unknown, the source of attackers and storms, whose deity was Anzu.

This is also reflected in the second occurrence of the name. Psalm 80 describes Israel as a splendid vine brought out of Egypt and planted in new land, now being ravaged by enemies:

יְכַרְסְמֶ֣נָּֽה חֲזִ֣יר מִיָּ֑עַר וְזִ֖יז שָׂדַ֣י יִרְעֶֽנָּה׃

Yekharsemennā ḥazīr miyyā‘ar, ve zīz sāday yir‘ennā

“ravaged by forest boar and devoured by the zīz sāday”.

According to Nini Wazana, in the symbolic language of the time, these two creatures correspond precisely to the two enemies that threatened Israel at the period when the psalm was composed: the wild boar representing Egypt and the ziz sadai representing the mountainous Assyria.

3.

The caption of our “goose illustration” says absolutely nothing about this entire three-thousand-year history. In fact, neither does the volume in which it appears.

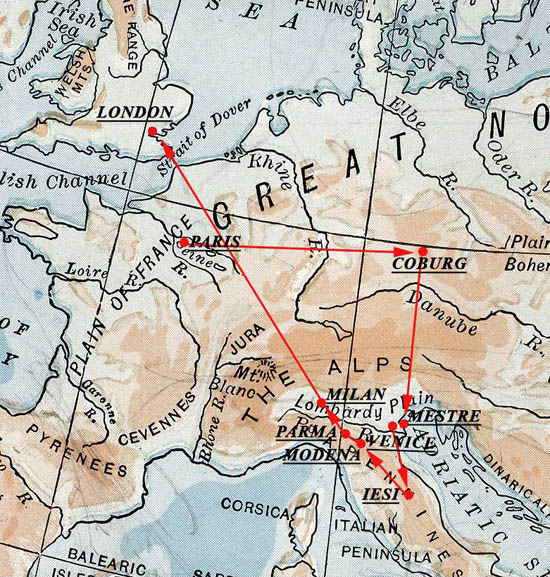

The image comes from a medieval codex known as the North French Hebrew Miscellany. The manuscript was assembled in Northern France between 1277 and 1298. Through a winding journey via Germany, Venice, Padua, and Milan, it finally reached the British Library in 1839 (Add MS 11639).

This massive codex, comprising 746 parchment folios (1,492 pages), contains the Torah alongside liturgical texts, the Haggadah, the earliest known Hebrew text of the Book of Tobit, legal texts, and poems by Moses ibn Ezra. A single scribe, Benjamin, copied the text, while the 49 miniatures were painted by multiple artists. Their digitized images were once available on the British Library website but have since vanished. The facsimile publisher Facsimile Editions, specializing in Hebrew manuscripts, has issued this codex, and all illustrations are visible on their site.

The images that mostly represent biblical scenes do not directly relate to the texts; they form a miscellany within a miscellany. Their models were drawn from contemporary Parisian Gothic manuscript painting, while the Bar Yochnei bird derives from contemporary Christian bestiaries.

The image of Bar Yochnei is paired with Solomon’s Judgment. Little direct connection can be discerned between the two. But flip a page, and on the next two folios we meet old acquaintances: Behemoth and Leviathan!

fol. 518b-519a. זה שור הבר ze shor ha-bar “this is the wild ox” = Behemoth, and זה לויתן ze livyātan “this is the Leviathan”

fol. 518b-519a. זה שור הבר ze shor ha-bar “this is the wild ox” = Behemoth, and זה לויתן ze livyātan “this is the Leviathan”

In the fifth century BC, Ezra and Nehemiah, returning from Babylonian exile and finalizing the Torah, may have purged from it the Babylonian and Canaanite creation myths, which depicted creation as a struggle between gods and the forces of chaos, deliberately replacing them with a monotheistic story in which the single God brings the world into being by His word alone, without opposition. Yet the vanquished figures of these myths found refuge in poetic works, the Psalms, and the Book of Job, as well as in the rabbinic tradition that interprets them—and there they have continued to live for three thousand years.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario