When you eat in the refectory of the Faculty of Arts, you know well you must not ask details about the source or composition of the objects shining on the plate, sometimes with names as stunning as “three-phase spine” or “Gordon Blue” (sic!), about whose nature and organoleptic qualities we promise not to tell more in detail. Beyond our professional obligations, however, our personal curiosity has also led us to try our teeth on some unusual meat. Now we present only a few examples from the USA, specifically from Texas.

In

Lubbock (TX) we ate rattlesnake. There they take the maximum advantage of these reptiles: they make boots, belts, jackets, shirts and amulets of their skin, and paperweights of their heads fiercely showing their forked tongues. Even their poison, a strong neurotoxin, is used in pharmaceutical industry and is an object of scientific investigation. So it is from Texas that we have brought this tin. I must say that the meat is quite tasteless and full of bones that have to be carefully removed.

“Dale’s Natural Rattlesnake. Smoked. Net Wt. 7.1/2 oz. 212 grams. Ingredients: Rattlesnake meat in water; salt, brown sugar, natural smoke flavoring. Serving suggestion: Remove bones and serve on crackers. This product is the result of 20 years experience and my personal desire to provide you with the highest quality product available. I hope you enjoy it. A fully cooked product. Packed by Dale’s Natural Products. Brighton, CO 80601”

It was no cheap delicacy: some fifteen years ago it cost us $ 13.99

(The can is perfectly preserved.)

In Texas we also tried a liquid of more dubious origin, and probably very limited production: armadillo milk.

“From the Heart of Texas. TEXAS ARMADILLO MILK. Vitamin D added. Ingredients: milk, disodium phosphate and carrageenan. 5 fl. oz. Produced and processed at the world’s only armadillo dairy near North Zulch, Texas from the world’s only herd of milking armadillos. Milked by hand by the world’s only armadillo milker. Warning: The effect of armadillo milk on humans is not documented. Our research team has noted that women sometimes develop a driving desire to go to the woods in the dark. Men sometimes become nocturnal and amorous and develop an uncanny ability to follow women in the dark. If these symptoms are noted, order more milk from C. A. J. Enterprises North Zulch, TX 77872”

In this case we have to seriously question the honesty of the canning company. The milk, although of the color of the

crema catalana, had the taste of the most ordinary cow milk. However, what we would like to try from the United States (at that time it was not yet on sale) is the following product. A third category after the hitherto mentioned two ones, the real and dubious food: mythological food.

Yes, indeed, an American company,

Radiant Farms has begun selling

unicorn meat, with such an overwhelming commercial success that the

National Pork Board has filed a complaint against the advertising slogan used to market the product, “The new white meat”, because it sounded too much like theirs: “The other white meat.” Both ones, in our view, unfortunate. In any case, the sparkling unicorn meat does not seem very white.

One of the most exciting food lists we have ever read is at the beginning of

the Arte cisoria (1423) by Don Enrique de Villena. It would have been surely of interest for Umberto Eco, had he remembered to include it in his

The Infinity of Lists, recently written and simultaneously translated by us into Hungarian. It is quite long, so we only copy the end of the items considered as “viandas synples”, simple food:

Afuera destas cosas dichas que se comen por vianda e mantenimiento e plazer de sus sabores, se comen otras por melezina; así como la carne del omne para las quebrantaduras de los huesos, e la carne del perro para calçar los dientes, la carne del tasugo viejo por quitar el espanto e temor del coraçón, la carne del milano para quitar la sarna, la carne de la habubilla para aguzar el entendimiento, la carne del cavallo para fazer omne esforçado, la carne del león para ser temido, la carne de la enzebra para quitar pereza. De las reptilias: las ranas para refrescar el fígado, las culebras para la morfea, los gusanos del vino para aguzar el estómago, las cigarras contra la sed, los grillos contra la estranguirria, e otras cosas desta manera por ayuda e reparaçión de la natura.

E aun algunas gentes comen desto por sabor, en sanidat; así como los turcos el cavallo, los çitas el omne, los françeses las ranas, los italianos las culebras, los andaluzes labradores las cigarras, en Canpos los gusanos del vino, en Vizcaya las lagostas, en Cataluña los labradores los osos, segunt que las tierras lo adebdant e la bivienda de la gente. E porque esto non es en cotidiano uso, paresçe estraño, pero cumple aquí dello tratar si el caso dello viñiese.

Apart from the above said things eaten as common food, both for livelihood and for the pleasure of their taste, there are others eaten as medicines, like human flesh for curing broken bones, dog meat to strengthen the teeth, the flesh of old badgers to remove the horror and fear of the heart, the meat of kite to remove the scab, the meat of hoopoe to sharpen the intellect, the meat of horse to strengthen people, the meat of lion to be feared, the meat of encebra [the extinguished Iberian horse] to remove laziness. Of reptiles: the frogs to refresh the liver, the snakes against morphea, the wine worm to sharpen the stomach, the cicada against thirst, the crickets against suffocation, and other things in the same way for the support and repair of nature.

And some people eat such things for the sake of taste as well as for health, like the Turks the horse, the Scythians human flesh, the Frenchmen the frogs, the Italians the snakes, the Andalusian peasants the cicadas, in Campos the wine worms, in Vizcaya the lobsters, the Catalonian peasants the bears, according to the circumstances of the places and the way of life of the people. And as this is not of daily use, it looks strange, but it was necessary to mention them for any eventuality.

It is striking that the text alludes twice, and without any valuation, to cannibalism, first as a remedy for broken bones and then as a favorite food of the Scythians.

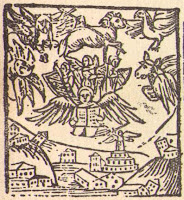

“Witches roasting a child”. Woodcut from Francesco Maria Guazzo’s Compendium

“Witches roasting a child”. Woodcut from Francesco Maria Guazzo’s Compendium

maleficarum, Milan: Apud Haeredes August Tradati, 1626. The use

of human flesh for witchcraft is fully documented in the

literature and iconography of the Renaissance.

These Scythian cannibals mentioned by Enrique de Villena must have been feasting like the ones shown in the following leaflet published by Adam Berg in 1573. It refers to a famine in Central Europe and illustrates the events of Reuss and Littau, where the starving peasants butchered the travelers and – as shown in the upper part of the image – took off the bodies of the executed evil-doers from the wheels and gallows to cook them.

Ein Erschröckenliche doch Warhaftige grausame Hungers nott Und Pestilenzische klag so im Landt Reissen und Littau fürgangen im 1573 Jar (Munich: Adam Berg 1573).

Ein Erschröckenliche doch Warhaftige grausame Hungers nott Und Pestilenzische klag so im Landt Reissen und Littau fürgangen im 1573 Jar (Munich: Adam Berg 1573).

It is also striking that, according to Enrique de Villena, Catalan peasants ate bears, apparently because of their abundance. No doubt, in the Catalan Pyrenees and in the dense Catalan forests

there were bears, but we have no reliable records on their use in the Catalan cuisine. At this point, the most spectacular bear recipe we can offer to our readers comes from the pen of Alexandre Dumas.

Dumas traveled in Russia nine months during the year 1858: this was one of those voyages that one can not cease to envy. He visited St. Petersburg, Moscow, Astrakhan, Baku, Georgia and the Black Sea coast, eating and drinking in the manner revealed by his mature portraits, and all facilitated by the invitation of a wealthy Russian family – our envy here already transforms into an eighth deadly sin pending documentation. This trip left plenty of traces in his

Dictionnaire de cuisine, where we read a eulogy of the tenderloins and hams of bear. Particularly tasty seems to be the bear ham that can be eaten cured (salted or smoked) or fresh and braised, as Dumas personally tried in St. Petersburg. However, the rich people of Germany had a predilection, he says, for a recipe imported from Russia by the cook of His Prussian Majesty, Urbain Dubois, who had previously been head chef of Prince Alexei Fedorovich Orloff. These are the paws of bear. The truth is that concerning this dish we have some doubts, as a favorite Russian dish of the Prussian royal house, whose recipe is transmitted by a chef from France (in particular, from Bouches-du-Rhône) must have been quite estranged from the reality of the good old Russian lands where the bear lives (even if the forests it inhabits are sometimes burned down). The recipe is this:

Clean well the [anterior] paws of the hair, then salt them and place them in a casserole, marinated. Leave them there for two or three days. Then put bacon and ham slices as well as a bed of vegetables in a pan, put the paw on this bed, and cover them with broth. Cook it for seven or eight hours on very low heat, adding broth as it is reduced. When they are well cooked, allow them to cool in their juice. Then take them out and cut them in four pieces, season them with cayenne, coat them with melted butter, and roast them for half hour over low heat. Finally, place them on a dish coated with hot sauce and some spoons of currant jelly.

Alexandre Dumas did not see his

Dictionnaire de cuisine in which for many years he kept collecting his gastronomic notes (he only started to arrange them in 1869). This recipe documents his friendship with the famous Urbain Dubois, and once we have investigated a bit, we have found that our doubts about its authenticity was unfounded. It appears that it was mentioned in a number of traditional Russian cookbooks and it was also in use in the Hungarian Carpathians, as it is attested by

this Hungarian recipe of “töltött medvetalp” (stuffed bear paw), provided with precise indications of protein, carbohydrates and other nutritional values for the sake of the lovers of reform cuisine.

We hope that these comments will not cause us

a penalty as it fell to the owner of the restaurant Pipiripao in Oviedo for announcing that he would include in his menu meat of bear and of grouse, both species being strictly protected. And rightly so.

Gennady Pavlishin’s illustration to the Siberian tale “How the animals changed their paws”

Gennady Pavlishin’s illustration to the Siberian tale “How the animals changed their paws”