Mayor hazaña que la mía fue, desde luego, la del director de circo que trasladó hasta la llanura húngara una ballena para exhibirla mientras se pudría lentamente en el tráiler de un enorme camión (no hay cajas de porexpán tan grandes ni suficiente hielo). Pero en aquel caso la presencia del animal marino acabó provocando un oscuro estallido de violencia extrema entre los vecinos del pueblo. La inquietante historia la filmó Béla Tarr en Armonías de Werckmeister (con guión de László Krasznahorkai, 2000).

A veces los peces se nos vienen encima en forma de lluvia, como se asombraba Séneca en las Naturales Quaestiones («Quid quod saepe pisces quoque pluere visum est?...», I, 6, 2-4), o Ateneo en Deipnosophistae («Ferunt etiam pisces de caelo decidisse, ut in Paeonia et in Dardania, atque in regione Chaeroneae...», VII, 331e-f); y luego a su estela tantos relatos plagados de mirabilia desde la Edad Media al Barroco: Isidoro de Sevilla (Etymologiae XIII, 7, 7), Alberto Magno, Cardano, Kircher... O por ejemplo Olaus Magnus en su libro sobre las regiones inexploradas del Norte (1555):

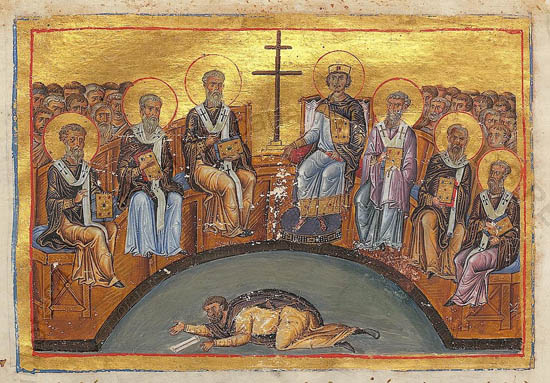

Que yo sepa nunca han llovido ballenas. Pero sí es bien conocido que estos animales son proclives a dar sobresaltos a las poblaciones costeras apareciendo por sorpresa en las playas y, con frecuencia, eligiendo una zona poblada para ir a pasar sus últimas horas y morir allí ante el espanto de la gente. Una de las historias más interesantes de este tipo podría ser la de la bestia a la que los súbditos de Justiniano I (527-565) bautizaron Porfirio y que aterrorizó durante más de sesenta años a todas las naves que se acercaban a Constantinopla. Lo cuenta Procopio de Cesarea en su Historia secreta y en la Historia de la guerra {{footnote:Véase un resumen en Anthony Kaldellis, 'A Cabinet of Byzantine Curiosities', Oxford University Press, 2017)}}, dando detalles sobre su enorme tamaño y ferocidad. Porfirio atacaba indistintamente a pescadores o navíos de guerra y los hundía de un coletazo. A pesar de los intentos de acabar con ella promovidos por el propio emperador (a quien lamentablemente no se le ocurrió rezar al san Rafael etíope), Porfirio solo cesó en sus fechorías un día en que, persiguiendo a unos delfines, embarrancó en unos bajos lodosos a la entrada del Mar Negro y ya no consiguió volver aguas adentro. Los ribereños, alertados, acudieron volando con hachas y cuchillos hasta el lugar pero con estos instrumentos apenas atravesaban su piel. Al final pudieron atarla y arrastrarla penosamente a tierra firme, donde la descuartizaron y muchos de ellos, allí mismo, montaron una alegre y abundantísima barbacoa. Cabe la duda de que esta bestia fuera realmente Porfirio, pero el caso es que desde aquel día ninguna otra ballena volvió a aterrorizar el Bósforo.

Hay algunas constantes curiosas en la literatura moderna cuando aparecen ballenas varadas o cadáveres de ballena, animales inmensos descomponiéndose sin que nadie sepa cómo deshacerse de ellos. Así, es recurrente convertirlos en símbolos de un poder en descomposición o de una situación social de tensiones larvadas e irresolubles que casi ni se saben verbalizar y cuya latencia contamina el aire y la convivencia de forma irremediable. Esa es la carga angustiosa del film de Béla Tarr y también está —en un grado menor y envuelta en su característica ironía— en la historia de Eduardo Mendoza La ballena (del volumen Tres vidas de santos, 2009) con una ballena muerta en el puerto de Barcelona a finales de los años '50.

Y también es el lejano telón de fondo de una historia, más próxima, que ahora quería recordar.

Colonia de Sant Pere, Artà a principios de los '70. Así la veía Rafel Ginard en sus Croquis artanencs (1929). Era un «...llocarró de cases diminutes, casetes de fira o de betlem, pobre i miserable, de terra magra i curta, on únicament hi prosperen els tamarells i un poc la vinya, sense gaire més patrimoni que vent salabrós, aigua de mar i sol implacable. El terrer és de call vermell, com si fos pastat amb sang i l'incendi solar que encara el crema i torra més de cada dia. Les figueres tenen les branques revellides i l'aspecte esquàlid de persones que han passada molta fam i tan mal a pler s'hi troben dins aquella tràgica marina que estan inclinades en actitud de fugir, com si diguéssim amb peu alt. No obstant, hi veureu una gota d'alegria enmig de la tristor aclaparadora: tapereres d'extraordinària magnitud que abriguen un redol com una era i qualque orla de canyes verdes que en passar-hi el vent sonen com una flauta. Els edificis de sa Colònia, disseminats en un bell desordre vora la platja descarnada i negra, plena de còdols, de recuits que són han pres un color roig tan rabiós que fa malbé mirar i contrasta d'una manera típica amb les sanefes de calç que engirentornen les finestres.» Aquí pueden verse muchas fotos antiguas del pueblo.

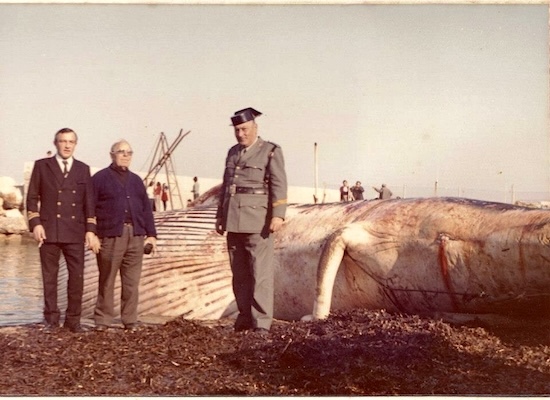

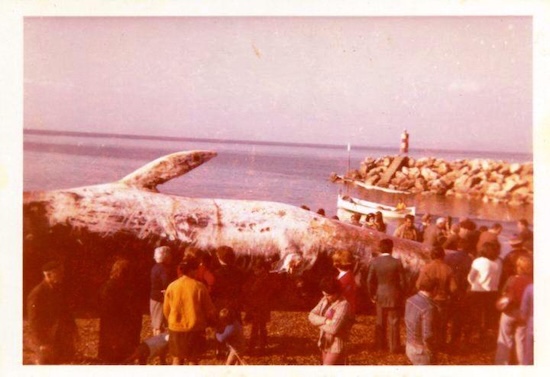

Estamos en el viernes 15 de enero de 1976. Desde hace menos de dos meses, Franco se está pudriendo en el Valle de los Caídos (en realidad lo estaba haciendo desde bastante antes de que lo enterraran) y en España nadie sabe muy bien qué va a pasar. Amanece en la Colònia de Sant Pere, un puertecito de pescadores de Mallorca donde no ha llegado aún la destrucción turística, muy cerca de Artà. El coronel de la guardia civil observa cómo en el agua, a pocos metros de la bocana, aparece un surtidor intermitente. En efecto, hay una ballena dando vueltas allí, cada vez más cerca del fondeadero. Es enorme. Y parece malherida. A media mañana dos barcas de pescadores, demasiado frágiles, se afanan temerosamente en evitar que el animal quede varado dentro del puerto, pero no consiguen moverlo. Hay mucha sangre alrededor. Deciden entonces que lo mejor será sacarla del agua y lo consiguen atándola con unos cabos por la cola. La ballena agonizante, sin fuerzas, solo resopla. Y seguirá viva y gemirá espantosamente cuando algunos chicos de la Colònia, junto a otros que han venido corriendo de Artà para ver el prodigio, se le trepen luego por encima. Es un jolgorio, el mejor preludio posible para la gran noche de Sant Antoni, del fuego, de la bendición de los animales y del demonio; estamos en el clímax festivo del invierno, especialmente en Artà y los pueblos del norte de la isla. A la noche, la ballena, un rorcual de unos 14 metros, está muerta, con todo su peso, sobre la escollera, adonde han coseguido arrastrarla. Y ya tenemos los ingredientes de una película que puede contarse de manera igualmente efectiva con los tonos neorrealistas, y hasta sarcásticos, de un Berlanga o con la densidad metafísica de los relatos con ballena desde Moby Dick. Aunque el carácter mediterráneo empuja con fuerza hacia la primera opción.

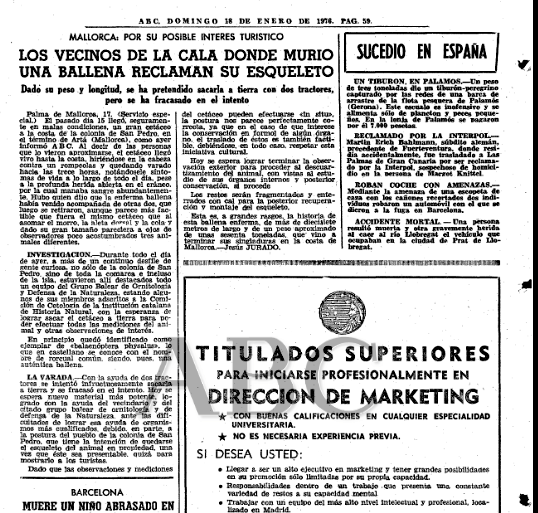

A los dos días de la aparición de la ballena saltan todas las preguntas. De quién es, quién se encarga de todo este lío, qué puede ganar el pueblo con esta carne y tanta grasa, y con los huesos... ¿podríamos colgar el esqueleto y hacer un museo que atraiga a los turistas? ¿Por dónde empezamos? La ballena empieza a apestar.

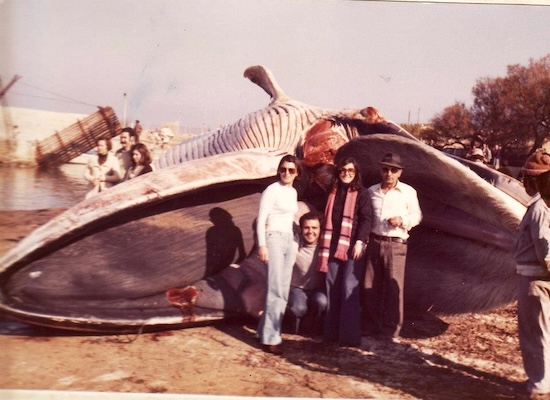

Menos mal que en Mallorca la gente suele ser de carácter pacífico y todo fue solventándose con buena voluntad y el benefactor punto de desidia que nos caracteriza. En otras islas una ballena varada ha provocado masacres, como la que se desencadenó hacia 1833 en Convincing Ground, Australia. Nuestro amigo Miquel Àngel Llauger acaba de publicar sus recuerdos de aquellos días que amenizaron la vida de la Colònia de Sant Pere. Tenía trece años y estaba entonces leyendo fascinado Cien años de soledad, así que su relato solo podía empezar así: «Molts d'anys després, davant el blanc cremat de la pantalla, l'escriptor seixantí recorda el capvespre remot en què son pare el va portar a conèixer la balena» (Díptic de la balena, 2025). Es una lástima que no se escribiera un reportaje en vivo de los hechos ni se conserven buenas fotografías. La verdad se relega de este modo a las memorias individuales y a la transmisión oral de quienes participaron —y de quienes creen que participaron— con las inevitables discrepancias y encendidas discusiones sobre quién hizo qué o decidió lo otro. Las fotografías recogidas en Fotos Antigues de Artà, con todo, dejan un testimonio extraordinario.

Y llegó el momento de ponerse en serio. Con sierras mecánicas el trabajo se convirtió en una auténtica carnicería. Grandes trozos de carne se llevaban al mar con la idea de que tan buen alimento para los peces beneficiaría la pesca. Unos cuantos se llevaron pedazos de carne para meterlos en el congelador. Otros decían que la grasa era tan buena como la manteca de cerdo.